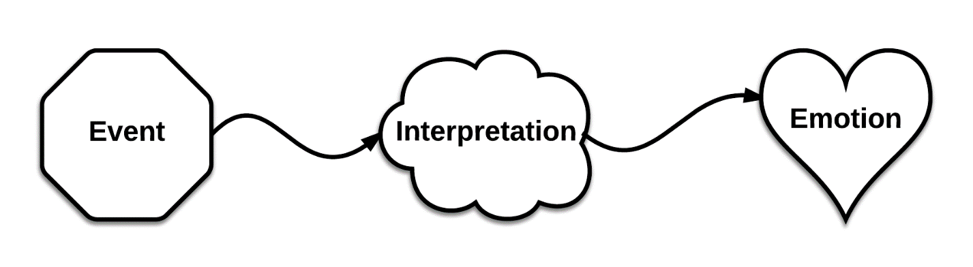

Our Interpretation System

Cognitive therapy is built on the following model of human emotions:

- We perceive an event or situation with our senses; we encounter

- We evaluate that event or situation; we interpret

- Our emotions align with that interpretation; we experience life as we’ve interpreted it.

Let’s call this our event-interpretation-emotion system. Here are some examples of how it can play out:

- Your boss sends you an email saying they need to speak with you. You guess that it’s about something bad. You figure that you’re probably in trouble. You worry that you might be getting fired. You feel anxious.

- Your spouse doesn’t do a chore that you’ve asked them to do. You assume that they’ve deliberately avoided doing it. You interpret this to mean that they don’t respect you. You get angry.

- Your friend doesn’t reply to your text message. You wonder why, and the answers you come up with are all bad. Perhaps they don’t value your friendship. Perhaps they don’t think you’re worthy of a response. Perhaps they’ve decided to cut off contact with you. You feel sad.

- Your teenager’s curfew-time comes and goes, and they’re still not home. You imagine that they’re out doing drugs or having unprotected sex, or that they’ve gotten into a terrible car accident. You get worried and upset.

Now, all of these interpretations are possible, but that doesn’t mean they’re likely:

- It’s also possible that your boss wants to ask you for advice, update you on a new policy, or give you a new project.

- It’s likely your spouse just forgot to do the chore you asked them to do, or they misunderstood the urgency of your request.

- Your friend is probably just really busy and meant to get back to you, but they got wrapped up in the drama of their own life and forgot.

- And your child, being a teenager, probably just lost track of time and will most likely come home safe.

Intervention

Cognitive therapy intervenes at Stage 2 in the event-interpretation-emotion system, aiming to improve our interpretations of reality. It asks us to question our automatic interpretations and consider alternatives. It encourages us to not only consider what is possible, but also what is likely. It asks us to remember that the catastrophes we imagine are, in fact, quite rare.

The interpretations we have are thoughts. Many of these are automatic negative thoughts that are overly anxious or defensive interpretations of reality. We shouldn’t immediately believe everything we think, and, instead, we should consider whether or not our interpretations are accurate and helpful. If they’re not, we should intervene by employing our thought bouncers, rejecting those interpretations, and coming up with better ones.

The Challenge of Recognition

The trouble is that our event-interpretation-emotion system operates so quickly that we often don’t have a chance to intervene. Thus, much of therapy is working to change our interpretations long after the system has produced unhappy emotions and unhelpful behavioral responses. Even though this doesn’t help us in the moment, it’s still good work to do for two reasons:

- One reason is that we spend a lot of time remembering past events, especially those that didn’t go well, and our unhelpful interpretations of those events cause repeated suffering. How many times have you mentally replayed old arguments, times you were wronged, personal slights, or mistakes you made? Wouldn’t it be nice to learn how to view those past events in a better light?

- The other reason this work is helpful is that the more we practice improving our interpretations after the fact, the better we’ll get at intervening in the moment. Many of the upsetting experiences we have in life repeat themselves: getting cut off in traffic, being criticized, spending an hour on the phone with a stubborn bureaucracy, and so on. If we buy into our automatic interpretations and get upset in the moment, fine, but we can reexamine them later, after we’ve gotten some distance from the situation and calmed down. Then, when we encounter a similar occurrence in the future, we might do better.

In addition, we can use mindfulness to strengthen our ability to slow down, notice our thoughts, and consciously choose more helpful interpretations. In this way, mindfulness practices, such as breathing meditation, support cognitive therapy. Indeed, there is such a thing as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.1

Alternative Interpretations

If you do manage to recognize the way in which you’re interpreting reality, either in the moment or after the fact, you then have the power to consider different interpretations. Here are some questions you might ask yourself when something upsetting happens:

- If I weren’t personally involved in this situation, how would I view it?

- How will I think about this a year from now?

- Will I even think of it at all a year from now?

- Is there anything funny about this?

- Am I overlooking anything?

- Am I exaggerating anything?

- How am I like that person who just upset me?

- Do I have control over any part of this situation?

- What steps can I take to make this sort of thing less likely to occur in the future?

- How could this have been worse?

- Is there a sense in which I actually just got lucky?

When something supposedly bad happens, it’s normal and natural to interpret it as something that is genuinely and entirely bad. But usually, if we look for it, we can find an upside. Sometimes misfortune is actually a blessing in disguise. Sometimes major problems bring big gifts.

And, most importantly, the benefits that come from adversity don’t come automatically. You have to take an active role in bringing them to life. There’s an element of self-fulfilling prophecy here: If you believe there is an upside to an unfortunate event, you’ll help create that upside. This comes down to making a conscious decision to interpret the event as not entirely bad, and then proactively working to make something positive out of it.

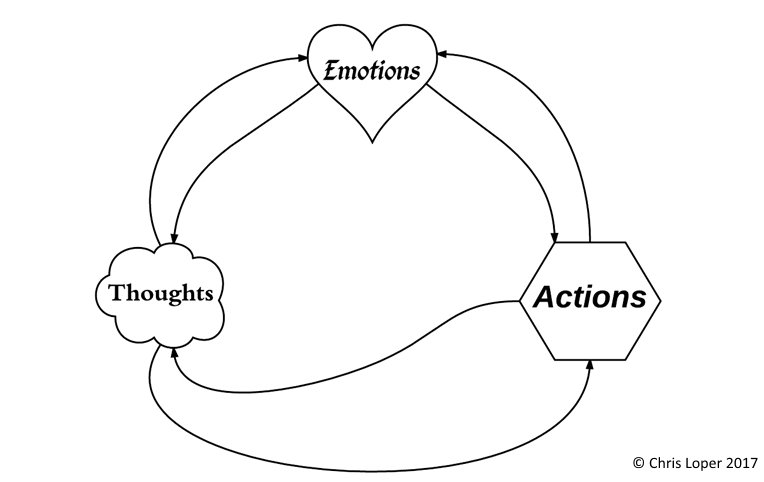

Behaviors Affect Interpretations

One way to fight an unhelpful interpretation of reality is to act in a way that is counter to that interpretation. You might think of this as the “do the opposite” principle. Feeling anxious? Adopt confident body language and calm breathing. Feeling selfish? Be generous. Feeling entitled? Express gratitude. Feeling angry at someone? Be kind to them.

By doing the opposite, you send a strong signal to your brain that you’re not buying into its default interpretation. As a result, you let go of that interpretation more readily, and your brain replaces it with a better one that aligns with your chosen actions.

Here’s an in-depth example:

If I’m given an extra task at work, I’m likely to interpret this to mean that I now have too many things to do. I’ll feel rushed and stressed, and I’ll feel like I don’t have time to help my coworkers or take a break. To counteract this, I can do the opposite of what my interpretation is calling on me to do.

I can go out of my way to do my coworkers little favors, which will communicate to me that I do, in fact, have time to spare. Researchers at the Wharton School of Business have confirmed that this technique reduces stress, offering the following advice: “‘When individuals feel time constrained, they should become more generous with their time—despite their inclination to be less so.’”2

And I can make time for rest and recovery during work, choosing slack over tension, which will further prove that I have time to spare. Because of self-perception, my brain will have to reappraise reality in light of my behavior. It will interpret the very same reality in a better way. I’ll stop believing that I have too many things to do and start believing that I’m capable of doing everything asked of me – so capable that I have time to spare. As a result, I’ll feel less rushed, less stressed, and less self-focused.

When you’re not in command of the feedback loop that controls your life, emotions tend to drive your behaviors. And these emotions are based on your interpretations of reality. But because emotions, thoughts, and actions are all connected in a bi-directional feedback loop, changing your behaviors will counteract both the unhelpful interpretations and the corresponding negative emotions.

This is why therapy not only looks at thoughts but behaviors as well, and is often referred to as cognitive-behavioral therapy. However, therapists aren’t generally focused on helping people actually change their behaviors using habit-formation strategies. They might suggest that you do something, but they probably won’t tell you how to actually do it. That’s where behavioral change coaching comes in handy.

Interpreting Our Emotions

In addition to interpreting the events that happen to us, we also interpret our emotions and let those interpretations dictate our actions.

For instance, if I’m feeling lazy, I might interpret that to mean that I cannot do any work (and then proceed to prove myself right). But I could interpret that same feeling of laziness to mean that doing my work will simply be more difficult than normal (and then proceed to get on with it).

Or take the feeling of resistance – you know, the feeling we get when we think about doing some work that we really don’t want to do. The default interpretation of resistance is that it means we shouldn’t (or can’t) do the work. A better interpretation is that resistance is a compass pointing us directly toward the work that we should be doing right now.

Or maybe you’re feeling sad, and you interpret that to mean you’re depressed. Therefore, you predict that you’ll feel sad for a long time, which makes you more sad – a self-fulfilling prophecy. Instead, you could interpret that feeling of sadness differently. Perhaps you’ve just had a tough week, and it’s normal to feel sad sometimes. You might interpret the feeling to mean that you need to reach out to a friend, or that you should go for a walk in the park, or that you want to watch a movie.

Look, I’ve been depressed, so I’m not suggesting that depression isn’t real. But I am saying that people commonly self-diagnose themselves as depressed when they’re experiencing normal – and temporary – sadness, and this overdiagnosis is actually an unhelpful interpretation of their emotions.

Lastly, you may recall that I took a bad ski fall a couple of years ago that left me with chronic knee pain. I could interpret this pain as a negative signal; I could get upset about the pain or feel sorry for myself. But the fall I took was so bad that I’m actually lucky that all I got was a knee injury. I should have died. So whenever my knee bothers me, I try to think about the fact that today is a bonus day.

What You Get to Control

The big idea here is that our emotions often feel out of our control – they just seem to happen to us – but we do have control over emotions because we can change our behaviors and our interpretations of reality.

It is only the things that happen to us that are outside of our control, at least once they’ve already happened. When an event has occurred, there’s nothing you can do to make it not have occurred. That’s outside of your control. But you can choose an empowering interpretation, born out of helpful mindsets, and you can choose to take positive action.

1 Wright, Robert. Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment. Simon and Schuster, 2017.

2 McGonigal, Kelly. The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It. Avery, 2015.