Do you ever procrastinate?

Yeah?

Oh good. I just wanted to make sure you’re human.

Procrastination is the #1 most common issue I work with people on.

6th graders avoiding their math homework? Check.

High school seniors putting off writing their college essays? Check.

24 year old’s neglecting their household chores? Check.

48 year old’s skipping workouts? Check.

All procrastinating.

But don’t get me wrong – I’m in no position to judge. I’ve done more than my share of procrastinating. Hell, I spent nearly all of my 20s putting off growing up and finding a career, along with innumerable minor tasks.

Procrastination has been a widespread problem since at least ancient times (the Code of Hammurabi actually delineated punishment for it),1 and genetic evidence suggests it’s baked into human nature.2 I’ve heard that there are people who don’t procrastinate, but I’ve never met one of them. Maybe Homo sapiens should really be called Homo procrastinatus.

So there we have the first major lesson about procrastination: You’re not alone.

And since just about everyone is doing it, you should probably stop feeling ashamed of yourself for procrastinating. It’s not helping. Instead, try giving yourself permission to be human. Procrastination doesn’t make you a bad person. As Craig Benzine put it, it just means you’re not doing a thing.3

The second takeaway from the fact that we all do it is the realization that some people have probably figured out how to do it less. Actually, scratch the ‘probably’ – they have figured out how to do it less. (You’re in luck – I’m one of those people!)

Yes, increasing your willpower helps,4 but that’s a long game. There are strategies and tactics you can use today to procrastinate less. This is a difficult problem, but the problem is not you, and there are mechanical solutions.

At the heart of these solutions is a revolutionary understanding of the relationship between motivation and action, so let’s start there.

Motivation and Action

Which comes first: motivation or action?

The answer is obvious, right?

Motivation comes first.

When I’m motivated, I take action. When inspiration strikes, I sit down to write. When I’m energized, I work out and do chores and knock out items on my to-do list.

Boom.

We all know intuitively that motivation causes action, and this is so obviously true that most people never question it. We believe we have to be motivated in order to take action, so we sit around waiting for inspiration to come, passing the time watching YouTube or playing video games or binging Netflix.

Totally understandable, but let me ask you this:

Have you ever felt unmotivated to do something – a workout, a chore, an assignment, a project – but then started anyway?

Yeah?

Well, that at least proves that you can do something without first being motivated to do it.

Follow-up question:

Has it ever happened that, after you started doing the work, you became motivated to continue? Have you ever found that your laziness seemed to evaporate after a short while, and you felt a sense of momentum driving you to keep going?

Yeah?

Me too. And that led me to the conclusion that action can cause motivation.

It’s certainly true that motivation causes action, but the reverse is also true, and that’s a really big deal.

It means we can create our own motivation. We don’t have to sit around waiting for motivation to arise – and we all know it rarely does – in order to take action. We can get started, and motivation will follow, which will make it easier to continue.

Dr. Timothy Pychyl, a leading procrastination researcher, says that this is the solution to procrastination:

“Let go of the misconception that our motivational state must match the task at hand. In fact, social psychologists have demonstrated that attitudes follow behaviors more than (or at least as much as) behaviors follow attitudes. When you start to act … you will see your attitude and motivation change.”5

To explain why this is true, we need to put the procrastination question on hold for a minute and learn about a psychological phenomenon called self-perception.

Self-Perception

Your brain isn’t quite sure who you are, how to feel, and what to think, so it’s constantly watching what you do in order to get a better sense of these things. And your brain wants there to be alignment between your identity, your emotions, your thoughts, and your actions, so it will try to align your inner state with your external behavior.6

This explains the findings that smiling tends to make you feel happier,7 and confident body language tends to make you feel more confident.8 Your brain watches you adopt these behaviors, and then the corresponding feelings follow suit.

Likewise, when you change your behavior, your brain will reevaluate who you are and update your identity accordingly. So if you’ve been saying to yourself, “I’m a lazy piece of crap,” but then you start doing work, your brain will begin to consider the possibility that you’re not a lazy piece of crap. If you do your work consistently, you will increasingly self-identify as a hard worker.

Thoughts, Emotions, and Actions

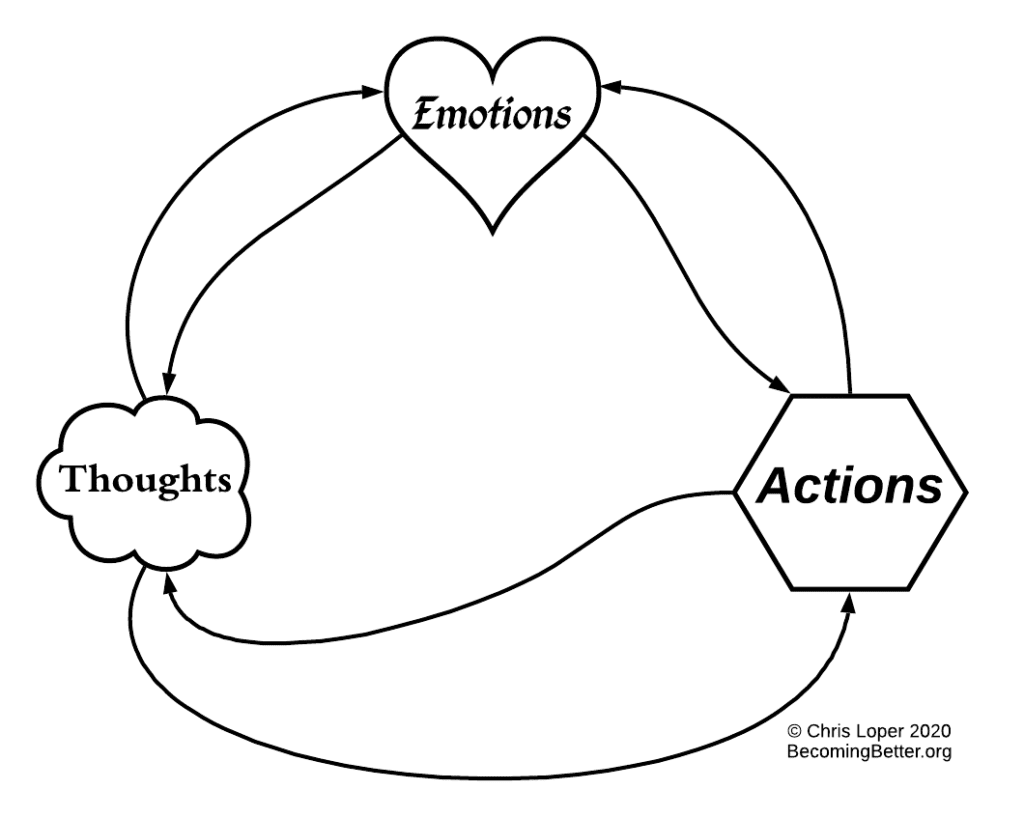

I understand self-perception as a bi-directional feedback loop connecting your thoughts, emotions, and actions. Each element influences the others: When one changes, the others change.

Feeling a certain way causes you to think and act a certain way. Particular thoughts inspire particular actions and encourage particular emotions. And, most importantly, new actions can trigger new thoughts and new emotions.

Let’s consider how this feedback loop might operate with respect to motivation.

Imagine you’re feeling motivated. Great news! This feeling probably coincides with thoughts of taking action:

- Productive or healthy things you want to do

- Reasons why it’s a good idea to do them

- Reasons why now is an excellent time to do them

With these thoughts and feelings propelling your forward, you get to work. And as you work, you demonstrate to yourself that you are capable of doing the work, justifying the thoughts and feelings you had at the start: See, it was a good time to get these things done.

Now imagine the opposite. You’re feeling lazy. Bad news. With this feeling tends to come thoughts of not taking action:

- Things you’d rather do than the work you ought to be doing

- Reasons why you don’t want to do that work

- Reasons why now is a bad time to do it

Demotivated by these excuses and your feeling of lethargy, you choose to put off your work. And as you lie on the couch, your brain watches you and feels justified: See, we really didn’t have the energy to do it.

Taking Control

It would be nice if you could just make yourself feel motivated whenever you feel lazy, but you can’t. No one can. Emotions are not directly controllable. But you do have control of the other components of this system, so you can influence your emotions via your thoughts and actions.

When your mind thinks of excuses to avoid doing your work, you can reject those thoughts. You can even argue against those excuses and generate reasons why now is, in fact, a good time to do the work. Writing out the reasons and keeping that list visible may also help.

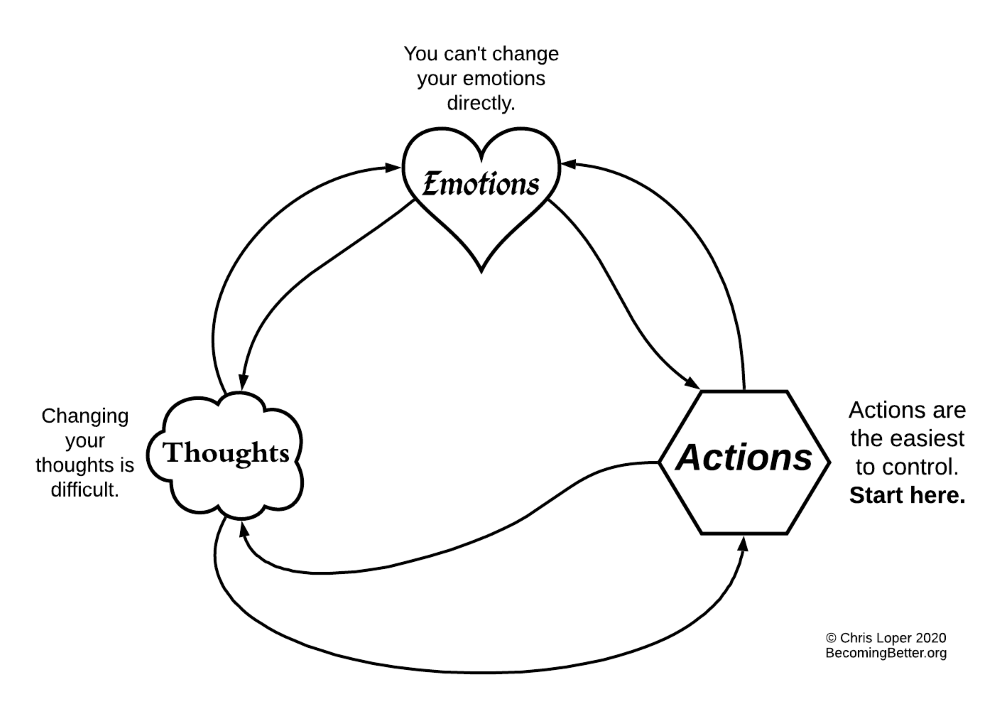

But for quicker, more powerful results, just start doing the work.

Action is more energetically expensive than thinking, which is why actions speak louder than thoughts. And, critically, we have much greater control over our behavior than we do over our thoughts. Many of our thoughts arise automatically, and fighting against these automatic thoughts is an uphill battle. It’s better to just start doing the work in spite of all your excuses and in spite of feeling lazy.

Productive Momentum

Remember Newton’s first law of motion – the law of inertia?

Well, for those of you who are not physics nerds like me, let me fill you in.

Newton observed that an object in motion tends to stay in motion, while an object at rest tends to stay at rest.

Applied to productivity, this law says that a person who is working tends to continue working, while a person on the couch tends to remain on the couch. Just as a ball rolling down a hill will continue rolling because it has physical momentum, a person who is hard at work will find it easy to continue working because they have productive momentum.

In terms of our feedback loop, taking action produces thoughts and feelings that make it easier to continue taking action. This, along with a few other elements to be discussed shortly, is why action causes motivation.

Once we get going, it’s not that hard to keep working. The difficulty procrastinators have is in overcoming the inertia we feel when we’re not working.

Just Start

“Motivation follows action. Get started, and you’ll find your motivation follows.” –Timothy Pychyl9

Think about the last time you started a workout when you didn’t feel like doing it. Compare how you felt right before you started and right at the beginning with how you felt after five minutes of exercise. If you’re anything like me, you felt a lot more motivated after you got moving. I often don’t feel like starting my morning exercise, but after a few minutes, I usually don’t want to stop. And you’ve probably had similar experiences with work projects, reading, and doing chores.

Procrastination usually begins with some combination of the following: I don’t feel like starting, and I’m thinking of excuses (“reasons”) to put off doing the work. The way I overcome this is by starting anyway. I decide to get going in spite of not wanting to. And then, in a short amount of time, I usually overcome my inertia and develop productive momentum.

So here’s how this usually goes:

- I don’t feel like doing the work.

- I decide to start anyway and commit to doing a small amount of work.

- I realize that it’s not as bad as I thought it would be.

- I think of reasons why now is, in fact, a good time to be taking action.

- I increasingly see myself as someone who is capable of doing the work.

- I feel proud of myself for doing the work.

- As I make progress, I feel good about the fact that I’m making progress, or at least I feel glad that I’m getting it over with.

- I start to feel energized.

- These positive emotions combine into a feeling of motivation, making it easier to continue.

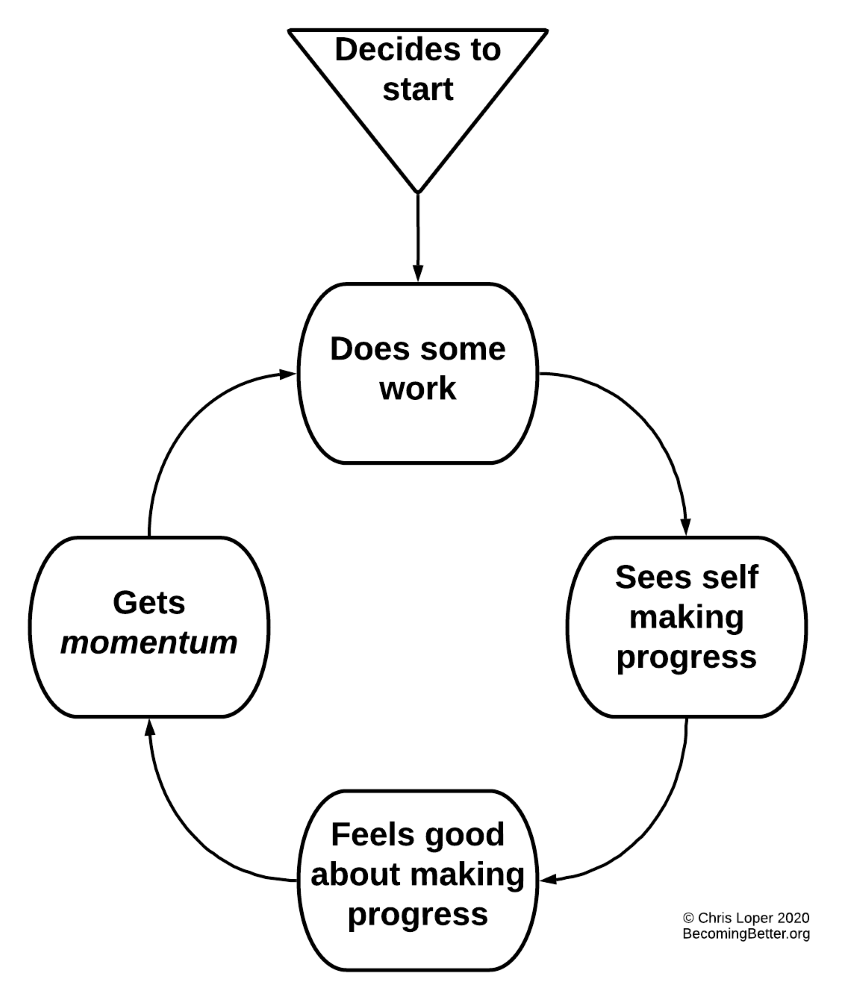

Surely you’ve had this experience many times. The trouble is remembering that this is what will happen if you start. To that end, here’s a simplified visual of this process, which I call “The Motivation Feedback Loop”:

The big idea here is that, although starting the work takes a lot of willpower, it won’t require nearly as much willpower to continue working after you begin. Starting is hard, but the work will get easier.

“Procrastinators often believe that to do something one has to truly want to do it—to be in the right mood, to feel inspired. This is not the case. Usually, to get the job done, it is enough merely to begin doing it—the initial action kick-starts the process and often brings about more action.” –Tal Ben-Shahar10

Now, you might be wondering, How long do I have to work before I start to feel some momentum? Well, it varies, but both research10 and my own experience suggest that it usually takes just five minutes.

The Five-Minute Takeoff

The Procrastination Research Group at Carleton University devised a simple strategy to kick-start the motivation feedback loop: the “five-minute takeoff.”10 Here’s how it works:

- Regardless of how you feel, commit to doing just five minutes of work.

- Promise yourself that at the end of five minutes, you are allowed to stop.

- Remove distractions, set a timer, and get to work.

When the timer goes off, there are three options:

- If it worked, and you’ve developed some momentum, congratulations – you’ve just generated your own motivation! Capitalize on this and keep going.

- If it didn’t work, and you’re still not feeling motivated, you might say to yourself, “Well, that didn’t kill me, so I guess I could do another five minutes.” Reset the timer, and keep working. Today, it might take more than five minutes to overcome your inertia. Or maybe you can power through this unpleasant task five minutes at a time.

- Or, if you really don’t want to keep going after five minutes, stop. You’ve made a deal with yourself that you would be allowed to quit after five minutes, and you need to honor that deal. If you force yourself to keep going when you’re absolutely hating the work, your brain won’t believe you the next time you try the five-minute takeoff, and this technique won’t be usable anymore.

If things go well, after five or ten minutes, you’ll find that you’re actually motivated to keep going. If things go really well, you might find yourself in a flow state. You may become so engrossed in the task that you lose track of time, do more and better work than you thought you were capable of, and actually enjoy doing it. This won’t happen every time, but there’s no way to get into flow without starting the work.

The Power of Starting Small

The five-minute takeoff is powerful because it makes starting easier. When we think about a huge work project or a 30-minute workout, our brains often put up a great deal of resistance. Because we don’t want to do the entire task, we avoid starting.

So when you say to yourself, “I only have to do five minutes,” you’re taking away a significant obstacle to beginning the work. By only committing to a small amount of effort, you’re tricking your brain into being okay with starting.

I don’t always set a timer to start small. If I need to go for a walk but don’t feel like it, I’ll just commit to making one lap around the block. I often find that, once I’m out there walking, I want to keep going. Or for my morning workout, I might say to myself, “This is just a two-song workout.” But when the second song ends and a third one starts, I often continue exercising.

This principle also applies to habit formation, and in turn, our tendency to procrastinate on starting healthy habits. You might recall that I developed a habit of meditating for 20 minutes per day by starting with three minutes per day. If you’re trying to start a healthy habit, don’t attempt to go from zero to hero; start small and build up gradually.

Make Starting Easier

Since starting is the key to overcoming procrastination, we’d be wise to make starting as easy as possible, and there are many ways to do that.

I’m a big fan of The 20-Second Rule, which states that making something just 20 seconds more convenient to do will increase your likelihood of doing it.11 There’s nothing magical about 20 seconds, though. Any increase in convenience will help, and the more the better.

Planning to exercise in the morning? Decide on your morning workout the night before, write out the plan, and lay out your equipment and exercise clothes so you can start without hesitation. Some people even sleep in their workout clothes.

Have a big project to work on tomorrow? Get your next day’s work set up the night before so you can jump right in. Remove obstacles and distractions. Open the word document and find the proper location. Gather the resources and organize them for easy access. Map out the steps in a clear plan.

The more time and energy it takes to get going, the more resistance you’ll feel. See if you can reduce the number of steps involved in beginning the actual work. See if you can make the first required step more convenient, even slightly more convenient. If you make starting 20 seconds faster, then you’ll save yourself from fighting 20 seconds’ worth of excuses. The more you delay, the more likely you are to not start at all.12

I’m also a big fan of warming up my willpower muscle before starting difficult work. I might do an easy chore to get myself in a productive mood before tackling a more difficult household task. Or I might start my writing session by copying some passages out of a book before trying to put my own words on the page. And I always start my day with a self-care routine that not only improves my brain health but also gets me using willpower right away.

Sometimes we procrastinate because we believe that the only work worth doing is perfect work.13 We fear that the work we’re about to do won’t be perfect, so we put off doing it. Thus, letting go of perfectionism will help you get started.

Other times we procrastinate because we aren’t sure how to begin. I see this often with students, who might avoid doing their math homework because they don’t know how to do it. If you then remind a student of their resources, get them to take notes, and provide a little instruction, they suddenly become eager to get it done.

I sometimes find myself putting off website projects because I don’t have the technical know-how to tackle them with ease. But if I watch an online tutorial or ask a friend for help, starting becomes easier.

So one source of procrastination is a lack of confidence in our ability to do the work.14 And how do you increase your confidence? By acquiring skills and knowledge.

Another way to make starting easier is to let go of the big picture. The goal of a work session should not be to finish the task; the goal should be to make progress on the task. If you’re feeling stuck, confused, or overwhelmed by what you have to do, follow Matthew Kelly’s advice and “just do the next right thing.”15

If the project has five steps, and you’re not sure how to do step 3, don’t let that stop you from taking steps 1 and 2. By the time you get to the dreaded step 3, you should have the momentum to overcome that obstacle.

Getting Side-Tracked

Most procrastinators are prone to getting side-tracked during their work and before even getting started (maybe instead of getting started), so minimizing distractions is a must.

The flip side of the 20-Second Rule is making distractions and non-work tasks less convenient so that you’ll be less likely to engage with them.

What non-productive things do you engage with when you’re procrastinating?

How can you make those things less convenient?

Hide them, move them, place obstacles between you and them. Design your environment to be conducive to productivity. Make the alternative tasks inconvenient or frustrating, “adding friction to the procrastination cycle and making the reward value of your temptation less immediate.”9

This is particularly important if your work involves a smartphone or a computer. In Solving the Procrastination Puzzle, Dr. Pychyl writes:

“Minimizing distractions is an important part of curbing our online procrastination. To stay really connected to our goal pursuit, we need to disconnect from potential distractions like social-networking tools. This means that we should not have Facebook, Twitter, email, or whatever your favorite suite of tools is running in the background on your computer or smartphone while you are working. Shut them off. Ouch. I know—it is really tempting to find some excuse to keep it a ‘business as usual’ approach here, but if you are committed to reducing your procrastination, this is something you really need to do. You must shut off everything except the program you need to do the task at hand.”5

I would add that you should not have distracting websites on your favorites bar, and you should delete them from your new tab screen. If you get distracted by Facebook or Netflix, don’t allow those sites to save your login information. If accessing your go-to distraction is kind of a hassle, you’ll find yourself less inclined to do it. You could even make your password a personal message that says “getbacktowork” or something similar.

Excuses

Now, as much as I love using The 20-Second Rule to make it easier to do my work, I have to be careful not to let my bias toward convenience be an excuse to avoid doing what I need to do. It’s not always possible to make getting started convenient, and it’s not always possible to make distractions and alternative tasks difficult to access, so sometimes I have to fight an uphill battle.

If you hear yourself thinking, Yeah I should do that, but it’s just not a very convenient time, you’re listening to your bias for convenience make an excuse to avoid doing the work.

That same voice often comes up with an impressive array of reasons why doing the work tomorrow would be easier than doing it today. But we all know from extensive experience that this voice is a liar.

It is almost never the case that tomorrow is actually a better time to do your work than today. That’s just wishful thinking. It’s not like you’re going to wake up tomorrow and suddenly find cleaning your house or doing your taxes exciting. And you’ll probably be just as busy, tired, and unmotivated tomorrow as you are today.

In fact, research shows that delay is likely to reduce your already paltry motivation.12 Conversely, as we’ve discussed, starting the work will increase your motivation.

Only rarely do the circumstances of tomorrow make doing the work easier than it would be today. For example, if you need to get some writing done, and there are noisy guests in your home today, but the house will be empty tomorrow, it will probably be easier tomorrow. The key here is to separate changing circumstances – which can actually happen – from changes in yourself – which will almost certainly not happen in the short run.

So don’t believe everything you think, and be prepared to argue against the inner voice that generates excuses. A great way to do that is to remember your reason for doing the work in the first place.

A Strong Why

Now, you might be thinking, If I could ‘just start,’ I wouldn’t be procrastinating in the first place!

Fair enough. Saying the solution to procrastination is to generate your own motivation by just getting started is sort of like saying the solution to being overweight is to lose weight.

So what gets you to start when you don’t want to?

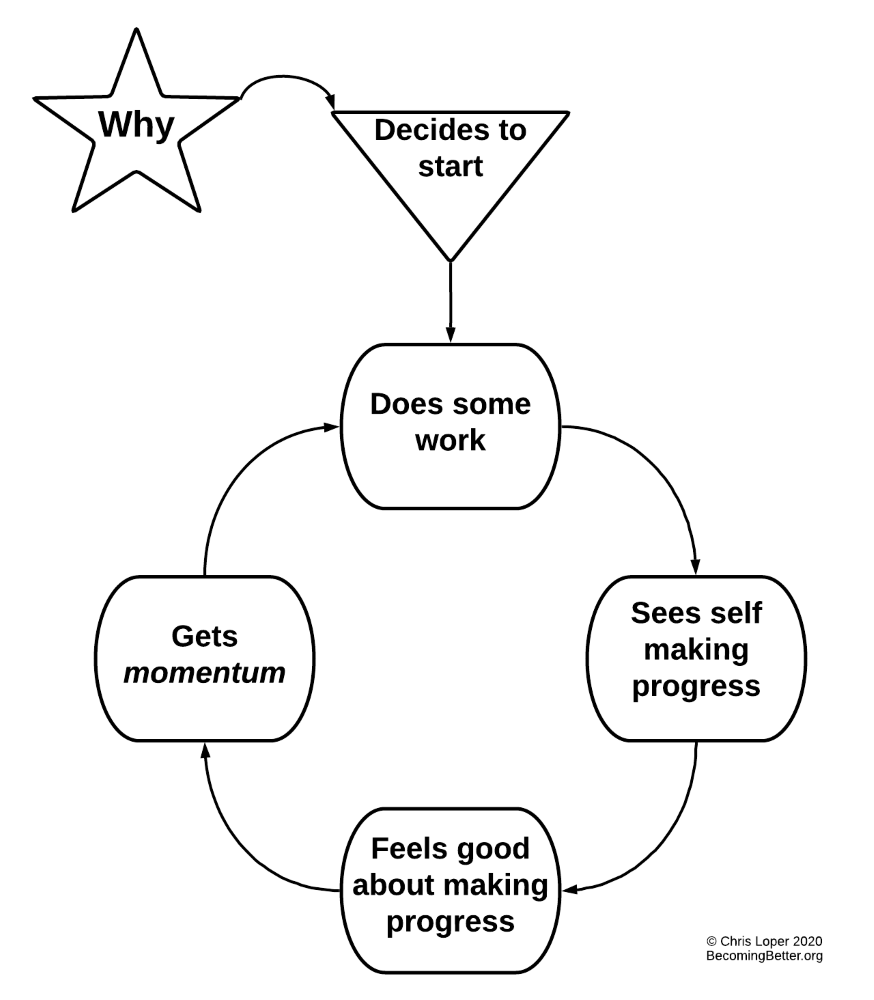

The answer is a strong why. You need to have a compelling reason to do the work. So here’s an updated version of The Motivation Feedback Loop:

Your why needs to be something positive, not a negative consequence, because negative emotions do not motivate action; negative emotions motivate inaction.16 And, in general, we’re much more likely to do something when we think about the benefits of doing the thing.12

So your why can’t be “because if I don’t, I’ll fail this class” or “because if I don’t, I’ll get fired” or “because if I don’t, I’ll get cancer.” Although those consequences are serious, they’re not motivating. Fear just leads to avoidance.

Instead, your why needs to be something you want, some benefit you’ll get from doing the work. Maybe that’s a good grade or a promotion. Maybe that’s a feeling of accomplishment or the satisfaction of doing a good job. Maybe that’s a vision of your future self, enjoying the fruits of your labor.

Sometimes you care about the task at hand because it’s intrinsically meaningful to you, but often the task at hand is a tedious but necessary step toward something you actually care about. For example, I recently started a tutoring company. Getting this set up required many tedious steps, such as getting a business license and building a website. I was able to get myself to do those things because I’m excited to help students in the community where I live.

A student who wants to become a doctor in order to save lives has a big, strong why that can help her get started when she’s struggling to find the motivation to memorize anatomy or study for the MCAT.

An overweight father who wants to be alive and healthy a decade from now when his grandchildren will be born has a big, strong why that can help him get started when he doesn’t feel like exercising.

So it’s essential to find ways to connect the work you don’t want to do today to something larger that you care deeply about. You’ll procrastinate less if your reasons for doing the work come from within rather than from without.17

The most powerful version of this, I believe, is a major, overarching reason why – a reason that transcends particular goals and the tasks associated with them. For me, that why is freedom.

What I want most is the freedom to design my own life, the freedom to discover my potential, the freedom to express my highest self, and the freedom to contribute. I want to use my hard work and resourcefulness to cultivate this kind of personal, financial, and psychological freedom.

It’s the reason I get up when my alarm goes off. It’s the reason I exercise, eat well, and meditate. It’s the reason I’m dedicated to self-education. It’s the reason I write. I know I’ll never be completely free. I know perfect freedom isn’t a place I can actually get to. But it does help to have a guiding star. I can keep heading in that direction, knowing that every step I take makes my life just a little bit better.

So, on my personal copy of The Motivation Feedback Loop, underneath the “Why” star, I’ve written the word “freedom” to remind myself of this goal.

But I’m not saying you should have the same overarching reason as me. I’m saying you should put some thought into what you really want out of life, and whatever it is, write that down.

By the way, I didn’t give you the full version of Newton’s first law of motion. It actually reads, “An object in motion tends to stay in motion, and an object at rest tends to stay at rest, unless acted on by an outside force.” For instance, a ball that’s sitting on the ground moves when you kick it.

For productive momentum, however, the story is a little different. We get going when acted on by an inside force – our reason why. We have to self-start and, in doing so, create our own momentum.

Practice Starting

Now, as with all things, overcoming procrastination is a skill you can practice. Utilizing the “just start” method in order to activate The Motivation Feedback Loop is a skill that becomes easier and easier the more often you do it.

As you repeat a behavior many times, it alters your identity. Practice this skill enough times and you might even stop self-identifying as a procrastinator. All of us – even you, my friend – are capable of becoming a hard worker.

Even more powerfully, if you practice this enough, your brain will start to learn that feeling like procrastinating is actually a sign to begin the work. You’ll start to catch yourself avoiding things, and then you say to yourself, “Oh, I’m putting this off. I’m procrastinating on this. I’m probably imagining that it will be worse than it will actually be and causing myself unnecessary suffering. So I should just get it over with.”

Steven Pressfield writes about how we feel the most “resistance” to doing our most important work.18 Therefore, resistance is a compass that points us precisely toward the thing that we most need to do. The only way to defeat resistance is by getting to work.

You can take these ideas and create if-then rules, such as:

- If I feel resistance to doing the work, I’ll do the opposite of what the resistance suggests.

- If I feel like procrastinating, then I will set a 5-minute timer and get started.

Long-time readers might recall the difference between bison and cows. When a storm rolls in, cows run away from the storm and get rained on for a long time because the storm chases them. Bison, on the other hand, charge the storm and get rained on for only a short amount of time because they run right through it.19

Your work is the storm. Resistance is the storm. The discomfort of the task is the storm. Don’t run away from it. Run at it. Be a bison, not a cow.

Conclusion

Here’s a quick recap of what we’ve learned today:

- Taking action creates motivation.

- Your thoughts and feelings will change after you start doing the work.

- Overcome inertia by committing to just five minutes of work.

- Make starting easier.

- Counteract excuses with a powerful reason to do the work – a strong why.

- At first, the practice of “just starting” will be hard, but it will become more natural with practice.

- Feeling resistance to a task is actually a sign that you should begin now.

In other words, don’t wait for motivation to come – make your own.

P.S. You’ll Need Reminders

When you’re feeling lazy, it’s easy to forget that you can overcome procrastination by creating your own motivation. So you’re going to need reminders. To that end, here are three PDFs you can download and print:

Put them up in your home office – or wherever you need to be reminded about how to overcome procrastination.

1 Knaus, William J. “Procrastination, Blame, and Change.” Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. Vol. 15, Iss. 5, Jan 1, 2000.

2 Gustavson, Daniel E., et. al. “Genetic Relations Among Procrastination, Impulsivity, and Goal-Management Ability: Implications for the Evolutionary Origin of Procrastination.” Psychological Science. April 4, 2014.

3 WheezyWaiter. “Why You Shouldn’t Feel Bad When You Procrastinate.” Oct 6, 2020.

4 Zhang, Shunmin, et al. “To do it now or later: The cognitive mechanisms and neural substrates underlying procrastination.” Wires Cognitive Science. 14 January 2019.

5 Pychyl, Timothy A. Solving the Procrastination Puzzle: A Concise Guide to Strategies for Change. Tarcher, 2013.

6 Wilson, Timothy D. “We Are What We Do: The best way to change is often to change our behavior first.” Psychology Today. Blog: Redirect. January 17, 2012.

7 Wenner, Melinda. “Smile! It Could Make You Happier: Making an emotional face—or suppressing one—influences your feelings.” Scientific American. September 1, 2009.

8 Cuddy, Amy. “How Your Body Language Shapes Who You Are.” TED Global 2012.

9 Lieberman, Charlotte. “Why You Procrastinate (It Has Nothing to Do With Self-Control).” The New York Times. March 25, 2019.

10 Ben-Shahar, Tal. Choose the Life You Want: The Mindful Way to Happiness. The Experiment, 2012.

11 Achor, Shawn. The Happiness Advantage: How a Positive Brain Fuels Success in Work and Life. Crown Business, 2010.

12 Steel, Piers, Ph.D. The Procrastination Equation: How to Stop Putting Things Off and Start Getting Stuff Done. Harper Perennial, 2012.

13 Flett, Gordon L., et. al. “Components of Perfectionism and Procrastination in College Students.” Social Behavior and Personality. Volume 20, Number 2, 1992, pp. 85-94(10).

14 Milgram, Norman A., et. al. “The procrastination of everyday life.” Journal of Research in Personality. Volume 22, Issue 2, June 1988, Pages 197-212.

15 Kelly, Matthew. Perfectly Yourself. Ballantine Books, 2006.

16 Sharot Tali. The Influential Mind: What the Brain Reveals About Our Power to Change Others. Henry Holt and Co., 2017.

17 Senécal, Caroline, et. al. “Self-Regulation and Academic Procrastination.” The Journal of Social Psychology. 135:5, 607-619. 1995.

18 Pressfield, Steven. The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles. Black Irish Entertainment LLC. 2012.

19 Vaden, Rory. Take the Stairs: 7 Steps to Achieving True Success. Perigee Books, 2012.