Today, I’m tackling a big topic: mindfulness. But wait! Before you run away, let me convince you that it’s worth reading and quash a bit of your skepticism.

Perhaps for you, the very word “mindfulness” evokes images of hippies or new-age wackos. Fear not, as I am neither of those things. This article will simply serve as a practical, down-to-earth guide that explains what mindfulness is and how we can benefit from it.

Researchers have shown that mindfulness may improve physical and mental health, the ability to focus, intelligence, and even creativity. It also improves how we handle stress and might even make us more generous. Mindfulness does these things not through mystical energy waves or oneness with the earth, but through physiological changes in the brain. These changes are brought about primarily through the exercise of meditation.1,2

But don’t take my word for it. Consider what Mark Williams, Professor of Clinical Psychology at Oxford, and Mark Pennman, Ph.D. in Biochemistry, have to say about the benefits of meditation:

“Numerous psychological studies have shown that regular meditators are happier and more contented than average. These are not just important results in themselves but have huge medical significance, as such positive outcomes are linked to a longer and healthier life. Anxiety, depression, and irritability all decrease with regular sessions of meditation. Memory also improves, reaction times become faster, and physical stamina increases. Regular meditators enjoy better and more fulfilling relationships. Studies worldwide have found that meditation reduces the key indicators of chronic stress, including hypertension. Meditation has also been found to be effective in reducing the impact of serious conditions, such as chronic pain and cancer, and can even help to relieve drug and alcohol dependence. Studies have now shown that meditation bolsters the immune system and this helps fight off colds, flu and other diseases.”3

That said, we’re only a couple of decades into researching mindfulness, the scientific community is not without its skeptics, and there is a great deal left to sort out.4

Some are concerned that mindfulness practices will be used as alternatives to proven psychological treatments, similar to how some people use “herbs” and “energy healing” rather than modern medicine. These worries, however, are misplaced so long as people are well informed. Mindfulness complements and supports two of the most well-regarded methods in modern psychology: cognitive behavioral therapy3 and acceptance and commitment therapy.5 So if you tell your therapist you’re also pursuing mindfulness in addition to counseling, he or she should be glad to hear it.

Others are tepid about mindfulness because of its association with religion. While the concept of mindfulness does come from Buddhism, it need not be understood or applied through a religious lens. I will quote some Buddhists because they have good ideas, but you don’t have to become a Buddhist to practice mindfulness or benefit from it. You can integrate mindfulness into any religious or philosophical tradition without losing any aspect of your current belief system. You could practice mindfulness as a Christian or as an atheist, or as anything else for that matter.

So what is mindfulness?

Mindfulness is a term that gets thrown around pretty often, but few people seem to have any idea what it really is. This is not their fault. Mindfulness is not something that can be easily described or distilled into a single sentence, though many have tried. This is because mindfulness is a multifaceted concept that can only be understood by simultaneously knowing what its parts are, and recognizing that the whole is greater than that the sum of its parts.

So what are the parts?

Mindfulness is the state of mind that combines:

- Presence

- Curiosity

- Acceptance

- Non-Attachment

Presence combines awareness of what’s currently going on and focus on what matters most.

Curiosity is an open-minded interest in learning the truth about the world and about ourselves.

Acceptance is the willingness to witness and deal with whatever truth we discover.

Non-attachment is a state of mind in which we let go of the need for particular outcomes and detach ourselves from our own thoughts and feelings.

Each component can be cultivated separately, and each has its own set of benefits, but they are ideally developed as a unified set of skills. They all support and complement one another, leading to the profound benefits of mindfulness as a whole: improved mental health, greater free will, and wisdom.

Neurologically speaking, mindfulness is the practice of keeping the prefrontal cortex (PFC) active. The PFC is the newest part of the human brain, located right behind the forehead, and it is the primary seat of the four skills of mindfulness. When we keep the prefrontal cortex active, we prevent older, more instinctual parts of the brain from taking control of our mind and our behavior. The brain is like a bunch of muscles, and mindfulness is one of the best ways to strengthen this critical ability. In fact, brain scans reveal that long-term practitioners of mindfulness have thicker PFCs.6

Mindfulness isn’t a black-and-white thing that you either have or don’t have. It’s a set of skills that you develop through practice. Everyone already has some degree or another of mindfulness. It’s something we acquire naturally through normal childhood development and growing up. Older children tend to have more mindfulness than toddlers, and adults tend to have more mindfulness than teenagers. But without deliberate training, few people progress very far past the level necessary for basic survival. To truly thrive, we have to go to the mental gym. More on that later.

Mindlessness

It may also be helpful to understand mindfulness by its opposite: mindlessness.7

Too often, we go about our days (and our lives) mindlessly going through the motions. We robotically wake up and drive to work, monotonously complete another routine workday, only to go home and apathetically watch TV. There were opportunities to notice beauty throughout the day, but in our mindlessness, we didn’t. There were many reasons to be grateful throughout the day, but we weren’t mindful of them, so we felt no gratitude. There were people we could have genuinely connected with, but we were mindlessly self-absorbed or distracted. Another mindless day passes, with nothing special noticed or created.

David Foster Wallace called mindlessness “the default setting” or “unconsciousness.” This is the state of mind in which we believe everything revolves around us, and in which we give in to the impulse to assume the worst about the world and other people. In “This is Water,” he says:

“If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and who and what is really important, if you want to operate on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to think, how to pay attention, then you will know you have other options.” 8

Examples of Mindfulness

As I said, we all possess mindfulness to some degree or another, so we’ve all experienced mindfulness, even if we didn’t know it at the time.

Mindfulness is losing yourself in the view of a sunset and temporarily forgetting about your troubles.

Mindfulness is noticing that you’ve become distracted during a conversation, and then bringing your attention back to the person you’re listening to.

Mindfulness is realizing that you’re getting irritable because you haven’t taken a break for hours, and then deciding to go for a walk.

Mindfulness is when you catch yourself playing out an imagined future argument with someone in your mind, and then stop yourself and return to the task at hand.

“Mindfulness is feeling the sun on your skin, feeling the salty tears rolling down your cheeks, feeling a ripple of frustration in your body. Mindfulness is experiencing both joy and misery as and when they occur, without having to do something about it or having an immediate reaction or opinion. Mindfulness is directing your friendly awareness to the here and now, at every moment.” –Eline Snel9

The “friendly” part is critical because self-compassion makes changing course easier. In her book, The Willpower Instinct, Stanford researcher Kelly McGonigal explains how mentally beating yourself up every time you notice you’re off course actually makes doing the right thing harder.10

Mindfulness Is About What You Do

Sitting in meditation may be the best way to cultivate mindfulness, and the work there is done in your mind, but that isn’t the purpose of mindfulness. The purpose is to improve how we act in the real world.

Thich Nhat Hanh is a world-renowned Buddhist monk who taught at Princeton and Columbia in the early 1960s. However, in 1963, he returned to his home country – Vietnam – to participate in nonviolent peace efforts.11

He explains:

“When I was in Vietnam, so many of our villages were being bombed. Along with my monastic brothers and sisters, I had to decide what to do. Should we continue to practice in our monasteries, or should we leave the meditation halls in order to help the people who were suffering under the bombs? After careful reflection, we decided to do both—to go out and help people and to do so in mindfulness. We called it engaged Buddhism. Mindfulness must be engaged. Once there is seeing, there must be acting. Otherwise, what’s the use of seeing?” 12

Now, let’s take an in-depth look at the four skills of mindfulness.

Presence

The foundational skill of mindfulness is presence. Presence means being fully engaged with whatever is currently happening, rather than thinking about the past, thinking about the future, or allowing yourself to be distracted. Presence is a combination of awareness and focus: awareness of what is going on around you and inside your own mind, and focus on that which is most important at this moment.

Focus is good, but only to a point. If taken too far, you become hyper-focused and miss important environmental cues. You fail to notice that you’ve dropped something, fail to hear someone calling your name, or fail to see an oncoming car. Awareness prevents this.

Likewise, awareness is good, but only to a point. If taken too far, you spread your attention too thinly. You’re unable to concentrate, and you’ll be inappropriately distracted by environmental stimuli. Focus prevents this.

So we need both. Presence is the skill of maintaining a balance between focus and awareness.

Why is presence helpful?

Well, the practical benefit of presence is that it makes us more effective.

For example, whenever I do something clumsy, it’s because I’m being unmindful: either I’m thinking two steps ahead of what I’m actually doing, or I’m thinking of something else entirely. By contrast, when I’m fully present, I perform activities with deliberate precision and coordinated fluidity.

Presence is also essential for learning, creating, and problem-solving. Jon Kabat-Zinn has pointed out that the modern world makes the skill of presence both more difficult and more important:

“The world nowadays is so complex and fast-paced that knowing how to ground oneself in the present moment is an absolute necessity to make sense of the world and to continue learning, growing, and contributing what is uniquely yours to contribute to this world.” 9

This is so much the case that we’ve come to refer to the inability to stay present as a “disorder” of the mind: ADD or ADHD (the final D in both stands for disorder). Whether or not such cases are truly disorders is questionable, but we can be sure that the ability to focus is paramount to success in the modern world.

“We live where our attention is. If attention wanders all over the map, our lives cannot help being scattered, shallow, and confused. By contrast, complete concentration is the secret of genius in any field. Those who can put their attention on a task or goal and keep it there are bound to make their mark in life.” –Eknath Easwaran13

Furthermore, presence, along with power and warmth, is one of the three skills shared by all charismatic people.14 Thus, mindfulness can lead to greater charisma, making you more likable and helping you connect with other people.

The other reason presence is helpful is that it makes us happier.

“If you’re present in the present it’s a present.” –Bliss n Eso, “Next Frontier”

A Harvard study of over 2,200 participants found that people spend about half of their waking life “thinking about something other than what they are actually doing,” and that this mind-wandering “consistently made them less happy.”15

The same research showed that happiness was more influenced by whether or not participants stayed present in the activities they were doing than by the nature of the activities themselves.15 In other words, you might be happier doing the dishes if you can stay fully present to the process of doing the dishes than you will be watching your favorite show if you’re distracted.

“It is mindfulness that makes the present moment into a wonderful moment, into a happy moment.” –Thich Nhat Hanh16

The study’s authors, Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert, summarized their findings as follows:

“A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind.” 15

This finding makes a lot of sense because thinking about the past is the primary way we come to feel sad, and thinking about the future is the primary way we come to feel anxious. Thus, it should come as no surprise that practicing mindfulness is an effective treatment for both depression and anxiety.1,2,3

Also, if the mind wanders while we’re experiencing something fun, pleasurable, or beautiful, then we fail to fully enjoy that positive experience. Joy arises when we’re fully immersed in something good such that we don’t miss the details. Mindfulness allows you to savor a delicious meal, relish in the beauty of the forest, or lose yourself in a favorite activity.

“The more present you are, the less you miss.” –Eline Snel9

Flow

Through his research on world-class performers and highly creative people, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi discovered the concept of “flow.” Flow is a state in which you are facing an important challenge that matches your skills, resulting in deep concentration, expert performance or insight, and profound enjoyment.17 People commonly experience flow when performing music, playing sports, writing, or solving puzzles, but it is not limited to those domains. Any activity to which we give ourselves fully can become a flow experience.

This is why I love to play games, ski, climb, teach, write, and cook: These tasks all require me to focus on the present and offer flow opportunities. This is also why I deliberately cultivate the ability to stay present: It allows me to experience flow more often. With practice, flow can be found in almost any activity.

“The mark of a person who is in control of consciousness is the ability to focus attention at will, to be oblivious to distractions, to concentrate as long as it takes to achieve a goal, and not longer. And the person who can do this usually enjoys the normal course of everyday life.” –Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi17

Does the value of presence mean that we should always be present?

No. It is sometimes wise to think of the past. Without thinking of the past, we could not learn from our mistakes and failures. But don’t dwell too long. Once the lesson has been learned, you can stop replaying the bad scene in your mind and return to the present. Likewise, it is wise to think of the future. Without this skill, we could not plan ahead. But once your plans have been chosen, you can stop living out the imagined scenarios of what might come and return to the present.

Does this emphasis on the present mean we should forget the past?

No. It simply means that we should not live our mental lives there. We may visit occasionally and enjoy some nostalgia, but we should not stay. Living is done in the here and now.

Does this emphasis on the present mean we should forgo our goals and live hedonistically for the pleasures of the moment?

No. Instead, the challenge is to bring our highest goals and deepest values to life in the present. This will sometimes mean enjoying the moment. But it will often mean practicing self-restraint and discipline, doing what’s right for others and for our future selves.

What gets in the way of presence?

This may be obvious, but the #1 thing that gets in way of presence is distractions. We can never eliminate all distractions from our lives, nor should we, but we can eliminate a great deal of unnecessary distraction that we simply allow into our lives. It’s all too easy to let notifications on our phones and computers annoy us like gnats all day long, steadily draining our capacity to focus and taking us out of the present.

Curiosity

The next component of mindfulness is curiosity. This trait goes hand-in-hand with presence: Being curious about the world encourages us to be fully aware of our present reality, and we cultivate focus by directing our curiosity toward the task at hand.

It also inspires us to notice more than we would otherwise notice, which can be both educational and enjoyable. Each moment is special, unique, and worthy of your full attention. Curiosity means acting like a child, eyes wide open, excited to see what the world has to offer. It means taking less for granted and noticing all of the wonderful, little details that are available for us to enjoy.

“There are no ordinary moments.” –Dan Millman18

Curiosity also entails open-mindedness. This means acting like a beginner, approaching the world with fewer assumptions, being less quick to judgment, and resisting the impulse to categorize and label everything.

One benefit of this is flexibility. Mindfulness makes us less rigid about what things are and how things can be used, simultaneously helping us avoid limiting beliefs and increasing our creativity.

Another benefit is that curiosity makes us better at learning. A closed mind cannot be taught, while a curious mind is like a sponge, eagerly soaking up knowledge.

Also, due to their open-minded curiosity, practitioners of mindfulness are more aware of the detailed characteristics of everything, and thereby notice more fine distinctions between things. They therefore find it harder to sort things into broad, oversimplified categories. Instead, they see more complex, overlapping categories; they develop a spectrum mindset.

This curiosity about the world around you is also meant to be applied toward yourself and your own mind. Thus, mindfulness includes the practice of self-reflection and introspection. As with your observations of the world, what you discover when examining your own mind might be unpleasant. But if we are truly curious, we will not look away. We must try to be open to whatever is there and avoid blocking things out of our awareness because they are unpleasant.

A key element of mindfulness is striving to experience reality fully, exactly as it is.19

Acceptance

That last part would be impossible to do without another critical element of mindfulness: acceptance.

The past has already happened, and it cannot be changed. We must accept that what has happened has happened. This moment is already here, and it cannot be changed. We must accept whatever we find in this moment. The future is uncertain, and we must accept that uncertainty. To do otherwise would be to argue with reality, and this would be absurd. Reality will win every time.

Now, acceptance doesn’t necessarily mean approval, and it doesn’t mean being spineless either. We should still take action to make a better future. Acceptance means approaching the here and now with honest awareness – being with reality, rather than resisting it. We may then choose to change ourselves or change our situation, or we may even choose to change the world, but we first have to realize that here and now, in this moment, reality is what it is.

Resisting the problems we find creates needless tension, frustration, or anger. But acceptance doesn’t eliminate the problems that cause those negative reactions. Rather, acceptance allows us to approach life’s challenges calmly and deliberately. Acceptance does not equal resignation. You accept, and then you act.

In fact, acceptance improves our actions because it informs them. We can’t successfully gather data if we turn a blind eye to everything we find unpleasant. We can’t learn from mistakes if we’re unwilling to look at them. We can’t change the things we don’t like about ourselves if we don’t understand them.

“You can’t fully examine something if you are busy rejecting its existence.” –Bhante Gunaratana19

An important benefit of acceptance is the reduction of suffering. Buddhist teacher Shinzen Young offers this equation:

“Suffering = Pain x Resistance” 20

Pain is inevitable. On the ride of life, it is the price of admission. But suffering is an emotional reaction to pain that comes from our resistance to the pain. If we can manage to accept the pain, our suffering will diminish. The physical pain will remain, but the psychological suffering can be eliminated. This, of course, does not mean we shouldn’t take steps to eliminate the pain, prevent its cause, or heal ourselves.

Sam Harris puts it this way, though I’m not sure acceptance is as “simple” (or easy) as he makes it sound:

“If you are injured and in pain, the path to mental peace can be traversed in a single step: Simply accept the pain as it arises, while doing whatever you need to do to help your body heal.” 21

Because we all experience little pains and problems throughout our days, we have many opportunities to practice the skill of acceptance. Another Buddhist teacher, Shantideva, writes:

“Putting up with little cares, I’ll train myself to bear with great adversity!” 22

In mindfulness, we practice the acceptance of unpleasant things over which we have no control – daily discomforts and inconveniences – so that when we are faced with a real tragedy, we will be strong enough to bear it.

Non-Attachment

Acceptance becomes easier as we learn the skill of non-attachment. This means not being psychologically attached to any particular state or result. To want some outcome to occur is desire, and this is okay. But to feel as though we need some outcome to occur is to be attached to that outcome, and this is problematic. If something is perceived as a need, we will not accept reality if we don’t get that thing.

For example, I could want to win a tennis match, try my hardest to do so, and lose. This might cause me to be unhappy for a bit, but not overly so. Or I could need to win the tennis match, try my hardest, and lose. This will cause me great suffering because I was attached to the outcome of winning.

In Mindfulness in Plain English, Bhante Gunaratana writes that, while in a state of mindfulness,

“You see that your life is marked by disappointment and frustration, and you clearly see the source. These reactions arise out of your own inability to get what you want, your fear of losing what you have already gained, and your habit of never being satisfied with what you have. … you see how superficial most of your concerns really are. … You see the way suffering inevitably follows in the wake of clinging.” 19

Non-attachment to outcomes is wise because you cannot control outcomes. You can only control what you do. Forces beyond your control may make the results you desire impossible, so it is unwise to stake your happiness on any particular outcome. All you can do is keep your eyes on the process.

Detaching Yourself From Thoughts and Emotions

A key element of non-attachment is separating ourselves from our thoughts and our emotions. Mindfulness teaches that we are not what we think and we are not what we feel. We are the observer and the director of our thoughts and emotions. Learning to detach from our thoughts and emotions leads to better choices and a happier life.

Approaching the mind in this way is quite different from what we normally and automatically do. Let’s take, for example, the experience of someone being very rude to me.

I might immediately think, That guy is a complete asshole! However, I will probably fail to notice that the thought I’ve had is really just a thought. And I will be absolutely sure that it is true. I will immediately believe without question that the man is, in fact, a complete asshole. In reality, I know nothing of the man or why he acted in a way that I perceived to be rude. Perhaps he is normally a saint but has just experienced a series of terrible injustices that have made him temporarily self-centered. Perhaps he suffers from a mental disorder of which I’m unaware. Perhaps I’ve completely misinterpreted the situation, and it is I who is being rude. If I don’t recognize that my conclusion about the man is just a thought, I won’t consider any other possibilities. This might make me upset, and, ironically, lead me to be rude myself.

In such a situation, I’ll probably also feel anger. But I will fail to recognize that my anger is just a temporary emotion. Instead, I’ll think to myself, I am angry! In doing so, I am literally identifying myself with my anger. If I can step back from the notion of being angry and recognize that I’m feeling angry, then the emotion will have less power over me. If I can further step away from it by thinking, I’m noticing that I’m feeling angry right now, I will have detached myself from that emotion, which will cause it to fade faster.

“Our habitual identification with thought—that is, our failure to recognize thoughts *as thoughts,* as appearances in consciousness—is a primary source of human suffering.” –Sam Harris21

Since you are not your thoughts, you can stop judging yourself for having thoughts you’re not proud of. The same goes for emotions. Human nature has endowed us with certain knee-jerk reactions and instincts than run counter to high-minded moral principles, logic, and compassion. We all have these encoded in our genes. It’s not bad to have them; it’s only bad to act on them. Give yourself permission to be human.

Negative thoughts are inevitable. They arise automatically. This is why Dr. Daniel Amen calls them A.N.T.s – automatic negative thoughts.23 We worry about the future, we mentally replay bad experiences, we complain, we judge. This is normal, natural, and totally okay. There are ways to reduce unhelpful negative thinking, but more important is to reduce rumination.

Rumination is when we revisit a thought over and over again. It comes from the word “ruminant,” which is a hoofed animal that eats grass. Thich Nhat Hanh explains:

“We’re constantly consuming our thoughts. Cows, goats, and buffalo chew their food, swallow it, then regurgitate and rechew it multiple times. We may not be cows or buffalo, but we ruminate just the same on our thoughts—unfortunately, primarily negative thoughts. We eat them, and then we bring them up to chew again and again, like a cow chewing its cud.” 24

Rumination on negative thoughts is strongly associated with depression, as Sonja Lyubomirsky notes in The How of Happiness: “The combination of rumination and negative mood is toxic. Research shows that people who ruminate while sad or distraught are likely to feel besieged, powerless, self-critical, pessimistic, and generally negatively biased.”25

If one is depressed, or if one simply wishes to become happier, learning to reduce rumination is key. Mindful awareness of our own thoughts is essential, and the practice of meditation is one of the best ways to detach from your thoughts and stop ruminating.

Related to this is choosing not to believe all your thoughts. Just because you’ve had a thought doesn’t mean it’s true. A major part of cognitive behavioral therapy is learning to argue against negative thoughts, refuting them with logic and evidence.26

A similar approach must be taken with emotions. We tend to have a very hard time remembering past emotions and predicting future emotions.27 As a result, we incorrectly conclude that the way we feel right now is the way we’ve always felt and the way we’ll always feel in the future. For those suffering from depression, this is a tragic miscalculation, as Harvard’s Ellen Langer pointed out in her book Mindfulness:

“When people are depressed they tend to believe they are depressed all the time. Mindful attention to variability shows this is not the case, which itself is reassuring. By noticing specific moments or situations in which we feel worse or better, we can make changes in our lives.” 7

I have a friend who is chronically depressed. When we talk about it, he explains that he hasn’t experienced any happiness, joy, or fun in the past several years. But I can recall many times when I saw him smiling a genuine smile or laughing aloud or expressing joyous excitement. The sad thing isn’t that he doesn’t experience these emotional states, but that he doesn’t recall them, perhaps because he doesn’t fully notice them when they’re happening. Mindfulness might help.

The Deeper Benefits of Mindfulness as a Whole

Taken as a whole, mindfulness is far greater than the sum of its parts. The individual components each come with their own benefits, but together, they can produce wisdom and grant us the power to change our lives.

Mental Health

Mindfulness can lead to deep insights about yourself, your motivations, and your patterns of behavior. This is surely part of the reason mindfulness makes such an effective complement to psychotherapy, and why mindfulness is associated with reduced depression and anxiety, and increased happiness and serenity.

In their book, Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World, Mark Williams and Danny Penman write:

“Mindfulness is about observation without criticism; being compassionate with yourself. When unhappiness or stress hovers overhead, rather than taking it all personally, you learn to treat them as if they were black clouds in the sky, and to observe them with friendly curiosity as they drift past. In essence, mindfulness allows you to catch negative thought patterns before they tip you into a downward spiral. It begins the process of putting you back in control of your life.” 3

Better Behavior

Feeling better is certainly an important benefit of mindfulness, but acting better is perhaps more important. Remember: Mindfulness is about what you do. By showing us the way things really are and granting us the freedom to choose, mindfulness improves our behavior. The power of choice is essential on the journey of becoming better, and mindfulness gives us that power.

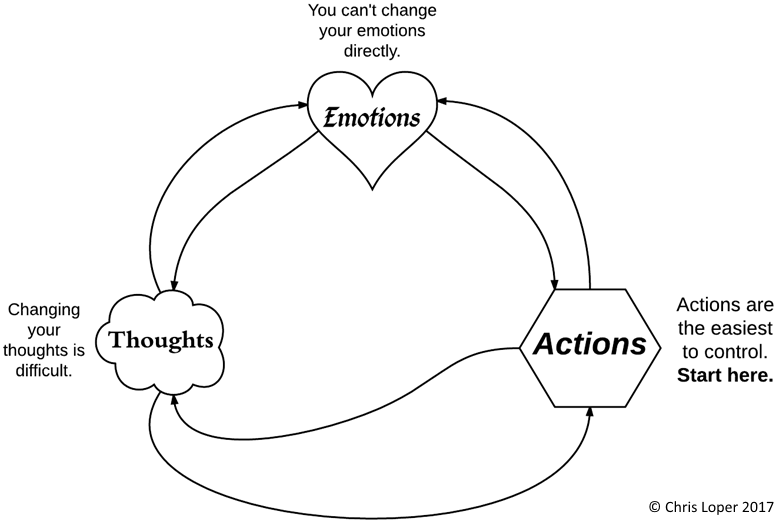

Each of the aspects of mindfulness – presence, curiosity, acceptance, and non-attachment – gives you the power to make better choices and increase the likelihood that you’ll exercise your free will. Awareness lets you know when you have a choice to make and what the options are. Curiosity provides the information you need to choose wisely. Focus gives you the power to execute that choice. Acceptance and non-attachment create the mental state necessary to respond rather than react.

“Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” –Viktor E. Frankl28

We can either live our lives this way:

STIMULUS —> REACTION

Or this way:

STIMULUS —> GAP —> RESPONSE

The latter leads to wiser, healthier, more ethical behavior. Mindfulness helps create and expand the gap between stimulus and response, giving us time to think about our values and exercise our free will. Without the gap, we have no free will. We just react on instincts, ingrained cultural programs, and old habits.

These reactions aren’t always bad, but they’re rarely chosen, so we can’t count on them to be good. Often, they’re quite harmful. In their book, Buddha’s Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love, & Wisdom, Rick Hanson, Ph.D., and Richard Mendius, M.D., argue that “there’s a kind of lizard-squirrel-monkey brain in your head shaping your reactions,” and that “modern life takes the jumpy, distractible “monkey mind” … and feeds it steroids.”29

Mindfulness helps tame the monkey mind and, in doing so, helps us express our incredible human potential. It also helps us stay on our best behavior. Mindfulness and ‘minding your manners’ go hand-in-hand.

“Mindfulness is like a safety net that cushions us against unwholesome actions. Mindfulness gives us time; time gives us choices. We don’t have to be swept away by our feelings. We can respond with wisdom rather than delusion.” –Bhante Gunaratana19

Given all this, it’s clear that mindfulness gives us greater authority over the feedback loop that controls our lives:

“In my view, the realistic goal to be attained through spiritual practice is not some permanent state of enlightenment that admits no further efforts but a capacity to be free in this moment, in the midst of whatever is happening.” –Sam Harris21

In other words, mindfulness helps you get out of victim mode and become an active agent. It helps you distinguish between what you can control and what you cannot, which helps you to direct your efforts more wisely.

In Sitting Still Like a Frog: Mindfulness Exercises for Kids (and Their Parents), Eline Snel writes:

“You cannot control the sea. You cannot stop the waves, but you can learn to surf them. This is the central idea underlying mindfulness practices. People have problems. Such is life. We all experience sadness and stress, and there are always things we simply have to deal with. When you are really present in such situations in life, without suppressing anything or simply wishing that they weren’t happening, you can see what might be needed. When you focus your attention and see the ‘waves’ for what they really are, you can make better-informed choices and act accordingly.” 9

Having greater control over your behavior gives you the power to change. Mindfulness, then, is a critical component of any serious behavioral change program. It is a counterintuitive truth that observing how things really are and accepting whatever you find makes it easier to change your life.

“The paradox is that we can become wiser and more compassionate and live more fulfilling lives by refusing to be who we have tended to be in the past. But we must also relax, accepting things as they are in the present, as we strive to change ourselves.” –Sam Harris21

Wisdom

For serious practitioners, the most significant benefit of mindfulness is wisdom. A deep state of mindfulness can produce profound insights into the human condition. But one does need to practice for years and achieve “enlightenment” to experience this benefit. For anyone, mindfulness can open the door to wisdom.

“In a state of mindfulness, you see yourself exactly as you are. You see your own selfish behavior. You see your own suffering. And you see how you create that suffering. You see how you hurt others. You pierce right through the layer of lies that you normally tell yourself, and you see what is really there. Mindfulness leads to wisdom.” –Bhante Gunaratana19

Cultivating Mindfulness

There are several ways to cultivate mindfulness which we’ll discuss in future posts. For now, try to find opportunities throughout your days to practice the four skills of mindfulness: presence, curiosity, acceptance, and non-attachment. And be patient and kind with yourself whenever you realize you’re being unmindful.

“Mindfulness is cultivated by a gentle effort.” –Bhante Gunaratana19

1 Seppala, Emma, Ph.D. “20 Scientific Reasons to Start Meditating Today.” Psychology Today. September 11, 2013.

2 Cho, Jeena. “6 Scientifically Proven Benefits Of Mindfulness And Meditation.” Forbes. July 14, 2016.

3 Williams, Mark, and Danny Penman. Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World. Rodale, 2011.

4 Stetka, Bret. “Where’s the Proof That Mindfulness Meditation Works?” Scientific American. October 11, 2017.

5 Serani, Deborah, Psy.D. “An Introduction to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.” Psychology Today. February 22, 2011.

6 Lazar, Sara W., et al. “Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness.” NIH Public Access. US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. February 6, 2006.

7 Langer, Ellen J. Mindfulness. 25th Anniversary Edition. Da Capo, 2014.

8 The Glossary. “This is Water.” Created with exerts from David Foster Wallace’s 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech.

9 Snel, Eline. Sitting Still Like a Frog: Mindfulness Exercises for Kids (and Their Parents). Shambhala, 2013.

10 McGonigal, Kelly, Ph.D. The Willpower Instinct: How Self-Control Works, Why It Matters, and What You Can Do To Get More of It. Avery, 2011.

11 Miller, Andrea. “Peace in Every Step.” Lion’s Roar. September 30, 2016.

12 Hanh, Thich Nhat. Peace Is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life. Random House, 1992.

13 Easwaran, Eknath. Strength in the Storm: Transform Stress, Live in Balance, and Find Peace of Mind. Nilgiri Press, 2013.

14 Cabane, Olivia Fox. The Charisma Myth: How Anyone Can Master the Art and Science of Personal Magnetism. Portfolio, 2013.

15 Sample, Ian. “Living in the moment really does make people happier.” The Guardian. November 11, 2010.

16 Hanh, Thich Nhat. No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming Suffering. Parallax Press, 2014.

17 Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row, 1990.

18 Millman, Dan. The Way of the Peaceful Warrior. H.J. Kramer, 2006.

19 Gunaratana, Bhante. Mindfulness in Plain English. Wisdom Publications, 2011.

20 Neff, Kristin, Ph.D. Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. William Morrow, 2011.

21 Harris, Sam. Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion. Simon & Schuster, 2014.

22 Shantideva. The Way of the Bodhisattva. Translated by the Padmakara Translation Group. Shambhala, 2006.

23 Amen, Daniel G., MD. Change Your Brain, Change Your Life: The Breakthrough Program for Conquering Anxiety, Depression, Obsessiveness, Lack of Focus, Anger, and Memory Problems. Harmony, 2015.

24 Hanh, Thich Nhat. Silence: The Power of Quiet in a World Full of Noise. HarperOne, 2015.

25 Lyubomirsky, Sonja. The How of Happiness: A New Approach to Getting the Life You Want. Penguin Books, 2008.

26 Burns, David D. Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. Harper, 2008.

27 Gilbert, Daniel. Stumbling on Happiness. Vintage, 2007.

28 Frank, Viktor E. Man’s Search For Meaning. Revised and updated. Pocket Books, 1984.

29 Hanson, Rick, Ph.D., with Richard Mendius, MD. Buddha’s Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & Wisdom. New Harbinger Publications, Inc., 2009.