The word “confidence” comes from the Latin con fidere, which means “with trust.” It’s the same etymology as the word “confide;” you confide in those whom you trust. To have confidence in yourself is to trust yourself – trust yourself to handle life’s challenges, trust yourself to get things done, and trust in your ability to learn and improve.

But it’s important to distinguish between false confidence, overconfidence, and true confidence. False confidence is a public façade put up to hide deep insecurities, and overconfidence is a dangerously unrealistic belief in your own abilities. True confidence is a reality-based belief about your own capacity to learn, improve, work, and succeed.

Psychologists use a different term for true confidence: self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is your belief in your own ability to handle challenges – the belief that you are an effective person. Self-efficacy can be understood as your answer to these four questions:

- Do you see yourself as capable of handling life’s challenges?

- Do you see yourself as resilient?

- Do you believe you can learn and improve?

- Do you believe that you can be successful?

This is distinct from self-esteem, which refers to the degree to which you like yourself. Both self-esteem and self-efficacy are associated with mental health, and both are important, but we must distinguish between the two. Self-esteem is more closely tied to happiness, while self-efficacy is more closely tied to confidence. So the manner in which you develop the right kind of self-esteem is different from the way you build self-efficacy.

We should further distinguish between the two types of self-efficacy: task-specific and general.

Your level of self-efficacy can vary from task to task and situation to situation. This makes sense because your competence at different activities varies as well. If you have a great deal of skill and experience with a particular task, you’ll have a strong sense of self-efficacy for that activity. For example, I am very confident skiing down a double black diamond, and I am very unconfident skateboarding down a flat road. The reason is simple: I am an expert skier and, at best, a novice skateboarder.

People also tend to have a general level of self-efficacy that they carry with them at all times. If you have high self-efficacy in general, you’ll be confident in most situations. Critically, even if you have never performed a particular task, you’ll be comfortable being a beginner and willing to give it a try. The certainty that you can figure new things out is at the core of general self-efficacy. And while it is important to develop task-specific self-efficacy for activities essential to your success, it is far more important to develop general self-efficacy for your life as a whole.

Another way to understand self-efficacy is through is opposite: helplessness. If you believe that there’s nothing you can do to improve your situation, that there’s nothing you can do to succeed, then you have zero self-efficacy. You are a passive victim of circumstances, rather than an active agent who takes charge of his own life.

Thankfully, this extreme is very rare. Self-efficacy, like most all psychological traits, lies on a spectrum, with complete helplessness on one end and total self-efficacy on the other. This means that it’s not an all-or-nothing trait, and self-efficacy can be developed incrementally. Every step in the right direction counts. So the appropriate question to ask yourself is not, “Do I have self-efficacy?” but “How can I increase my self-efficacy?”

Why Self-Efficacy Matters

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of self-efficacy. The Stanford psychologist who pioneered this concept, Albert Bandura, said:

“People who regard themselves as highly efficacious act, think, and feel differently from those who perceive themselves as inefficacious. They produce their own future, rather than simply foretell it.”1

In other words, they write their own story.1 Those who have true confidence are much more likely to pursue big goals, take necessary risks, and otherwise play to win. When you have high self-efficacy, you’ll be more resourceful, more willing to try again after a failure, and more open to using mistakes to learn. People with high self-efficacy also tend to have more motivation and procrastinate less than those with low self-efficacy,1 which makes sense: What could be more demotivating than believing you don’t have what it takes to succeed?

Not surprisingly, self-efficacy leads to persistence and resilience in the face of difficulties.2 People with low self-efficacy tend to avoid their problems, while people with high self-efficacy face their problems head-on.3 This is because seeing yourself as capable of handling something difficult causes you to perceive the obstacle as a challenge rather than as a threat. This, in turn, produces a better stress-response.4

Research shows that self-efficacy helps us deal with a variety of psychological problems.3 Low self-efficacy is associated with anxiety and depression, while high self-efficacy is associated with life satisfaction and helps people overcome difficulties like eating disorders and abuse.3

Since behavioral change is one of the most difficult things we can undertake, having a generally high level of self-efficacy should make change and growth more likely. Indeed, research shows that people high in self-efficacy are more likely to engage in healthy behaviors and less likely to engage in unhealthy ones.3

All in all, self-efficacy is clearly one of the foundations of a healthy, happy, and successful life. So how can we develop greater self-efficacy and thus build true confidence?

What Doesn’t Work

The most important thing to know about self-efficacy is that you can’t fake it. Self-efficacy is the reality-based belief you hold about how able you are to handle life’s challenges. So lying to yourself about what you’re capable of doesn’t help.

In other words, self-efficacy is not developed through positive thinking.

University of Pennsylvania professors Karen Reivich and Andrew Shatté explained the problem with this approach in their book, The Resilience Factor, and although they use “self-efficacy” and “self-esteem” interchangeably, the message is clear:

“The worst possible way to build someone’s self-efficacy is to pump them up with you-can-do-it platitudes. At best, putative self-esteem-enhancing slogans and motivational talks do nothing. At worst, they actually further undermine resilience and effective coping. Why? Because self-esteem is the by-product of doing well in life – meeting challenges, solving problems, struggling and not giving up. You will feel good about yourself when you do well in the world. That is healthy self-esteem. Many people and many programs, however, try to bolster self-esteem directly by encouraging us to chant cheery phrases, to praise ourselves strongly and often, and to believe that we can do anything we want to in life. The fatal flaw with this approach is that it is simply not true. We cannot do anything we want to in life, regardless of the number of times we tell ourselves how special and wonderful we are and regardless of how determined we are to make it.”2

Reivich and Shatté are, by the way, positive psychologists, and their admonition against irrational positive thinking should serve as a reminder of what positive psychology really is: the study of what works.

Just as false confidence and overconfidence neither reflect nor create true confidence, positive thinking will not produce self-efficacy. Similarly, the only optimism that is actually functional in the real world is realistic optimism.

Henry Ford was (mostly) wrong.

The following quote is probably the most famous line ever penned about confidence, and it is almost completely wrong:

“Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right.” –Henry Ford

As nice as that sounds, it fails to mention that thinking you can do something is only right if you can actually do that thing! If you don’t have the skills or the strength to do it, you’re going to fail, no matter how much you believe you can do it.

Thinking that you can when you really can’t is overconfidence, and that’s not what we’re after. An amateur hiker should not attempt to climb Mt. Everest just because he has deluded himself into thinking he can. And I should not try to ride my bicycle while juggling.

Most of the time, we believe we’re capable when we actually are capable. So the solution to low self-efficacy isn’t positive thinking – it’s the acquisition of skills, knowledge, and strategies. What actually works is learning “the tools to solve the problems in your life and to meet the challenges that confront you,” and then applying them.2

Become capable, and then, when you think you can, you will be right.

What Ford Got Right

As I said, Ford was mostly wrong. There are a handful of issues that can lead people to have low self-efficacy when they are actually quite capable. These are the problems of thinking you can’t when you really can.

Some people suffer from anxiety disorders that make them overly nervous or overly self-critical. Often, these people will believe themselves to be incapable of handling situations for which they do, in fact, have adequate skills. Addressing anxiety issues, then, should increase self-efficacy.

Perfectionism can also get in the way of self-efficacy. It’s hard for a perfectionist to feel truly effective because nothing he does is ever good enough. The perfectionist sets the bar for success impossibly high (since perfection is an ideal that doesn’t really exist) so he’ll never think that he can succeed. Click here for an in-depth look at why perfectionism is harmful and how to overcome it.

The belief that only perfect performance is good enough is an example of a limiting belief. Limiting beliefs are false notions we have about ourselves or about the world that hold us back from reaching our potential. Ideas like “It’s supposed to be easy, so I must not be a math person” or “I’ll never have the willpower to get in shape” are invisible shackles that people place on themselves for no good reason.

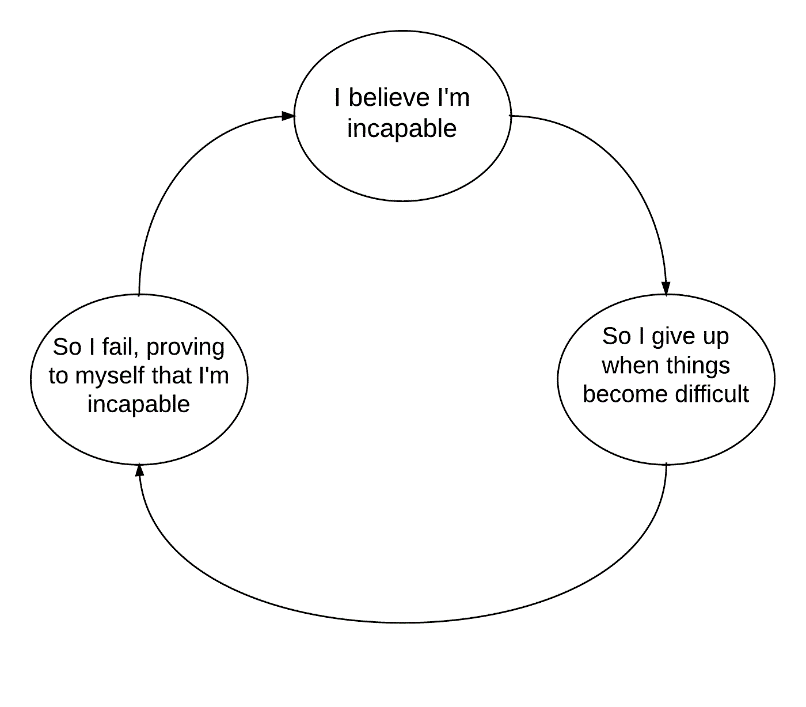

These false beliefs are so demotivating that they wind up proving themselves right. They create a sense of helplessness and hopelessness that prevent people from putting in the work that would lead to success. In other words, limiting beliefs are self-fulfilling prophecies.

Often, these come in the form of labels like “lazy” or “stupid” or “unathletic.” When we assign one of these labels to ourselves, we’re implicitly saying that these are all-or-nothing traits and that there’s nothing to be done about them. When we self-identify with one of these negative labels, we’ll tend to behave in a way that is consistent with the label, and thus reinforce it, making it seem true even though it is not.5

The worst set of limiting beliefs someone can hold are those associated with the “fixed mindset.” People with a fixed mindset believe that all their abilities are determined by genetics and therefore unchangeable.6 They don’t believe that putting in greater effort, learning new skills, practicing, or trying different strategies could possibly be helpful.6 So if they cannot currently succeed at a given task, they believe that they will always be incapable.6

If you have a fixed mindset, you’ll believe that persisting in the face of difficulty is a waste of time, so when things get hard, you’ll quit. And in quitting, you’ll fail, thus proving yourself right:

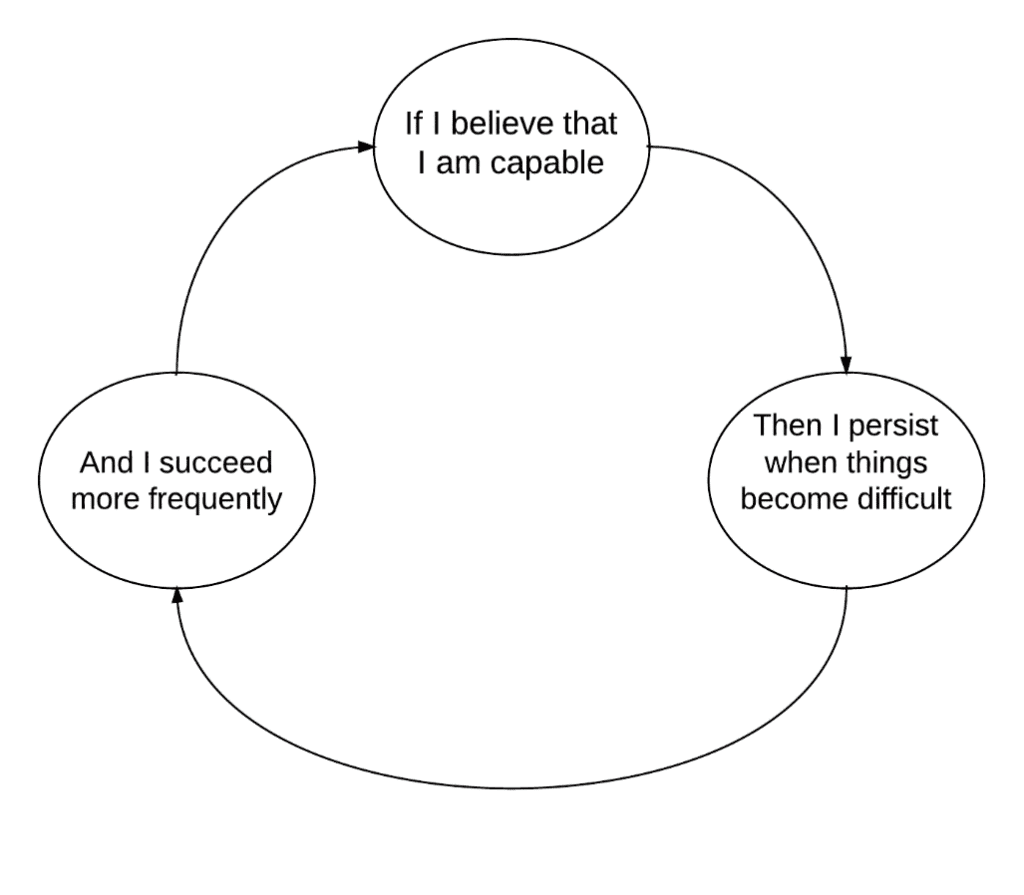

From this, we can see that the best way to read Ford’s line – “Whether you think you can or think you can’t, you’re right” – is as a statement about long-term abilities. If you can’t do something today, but you believe that you’re capable of learning and improving, you’ll put in the work to become capable in the future. If you believe you’re able to handle a challenge, you’ll persist, keep trying, seek out solutions, otherwise work your way to success:

Here are Reivich and Shatté on this idea:

“People high in self-efficacy stay committed to solving their problems and don’t give up when they find that their original solution doesn’t work. They are more likely than people who doubt their ability to cope to try new ways to solve a problem, persisting until they find a workable answer. And, by solving problems, their confidence is enhanced, which in turn increases the likelihood that they will persevere even longer the next time they are faced with a challenge.

In contrast, people who don’t believe they have the ability to bring about good things in their lives are more passive when faced with a problem or when placed in a new situation. They shy away from new experiences – taking on a new hobby, applying for a new job, joining a social group – because they assume that they are unequipped to meet the challenges that the new situation will bring. When a problem arises at work or in the family … they hang back and rely on others to search for solutions. If they are forced to solve a problem themselves, their lack of confidence causes them to give up at the first sign of difficulty. This too becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Each time they give up or fail to solve a problem, the belief that they cannot handle the pressures of life is reinforced and their self-doubt increases.”2

The opposite of a fixed mindset is a growth mindset. People with a growth mindset know that the human brain grows and rewires with experience, allowing us to adapt and improve.6 They know there’s value in learning from the examples of others and trying new strategies.6 If they can’t do something today, they’re inclined to say, “I can’t … yet.”6 They believe that many of the things we commonly mistake for innate talents are really skills you can learn and practice.6 Even “traits” like creativity, charisma, and willpower are learnable skills.

While the growth mindset is correct, and it is a powerful antidote to limiting beliefs, it doesn’t mean you can do anything. It just means you can improve at anything. No matter how hard I work, I’m never going to be in the NBA. I’m 33 years old, I have almost zero basketball experience, I have some injuries that limit my physical abilities. But I could definitely improve at basketball. With a few years of practice, I could become a decent player.

What Actually Works: Task-Specific Self-Efficacy

The basketball example is a case of task-specific self-efficacy. If I want to improve my feeling of self-efficacy on the court, I should practice dribbling, passing, and shooting. I should exercise more, train with a team, and get coaching. Developing task-specific self-efficacy is simple: Learn strategies, practice skills, build relevant strength, and get help. This applies to everything from computer programming to calligraphy to carpentry.

Develop skills. Learn and practice.

Use role models2 and coaches to improve.

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Get help from experts.

Master the tools of your trade.

Create an environment conducive to taking positive action.

Get the equipment you need. Eliminate distractions. Put up helpful reminders to keep you in the right mindset. Apply The 20-Second Rule.

Push your limits and learn from your mistakes.

Don’t berate yourself for struggling. Struggling is essential for growth. And so is self-compassion.7 Applaud yourself for getting back up, dusting yourself off, and trying again. Remember that mistakes and failures are powerful learning opportunities.

Do it the hard way.

Deliberately challenge yourself by doing things the hard way. I became a better skier overall when I mastered skiing on one ski. Challenge yourself in a variety of ways, and you’ll become increasingly skilled and increasingly confident. When you handle difficult things, self-perception causes you to see yourself as increasingly capable of handling challenges. Doing hard things is the only way to get the reference experiences you need to see yourself in this way.

Choose a Process-Based Identity

Don’t expect short-term results. If you’re committed to developing your self-efficacy for an important task, you have to be committed for the long-run. You’ll need to keep your eyes on the process and stop worrying about whether or not you’re performing well. For example, instead of worrying about whether or not you’re a good writer, write every single day. Choose a process-based identity.

What Actually Works: General Self-Efficacy

My approach to building general self-efficacy is mostly about developing character. Here are some approaches you can try:

Practice generosity.

Being generous is a way to prove to yourself that you are, in fact, capable of being helpful, so it increases your self-efficacy.

Use your strengths and correct your weaknesses.

We all have strengths, but we don’t all use them regularly. Be aware of your strengths, grow them, and use them often. Likewise, we all have weaknesses, and they diminish our self-efficacy. You can increase your confidence by correcting your weaknesses and by compensating for them strategically. Are you normally disorganized and brain-dead in the mornings? Then get things sorted out the night before and develop a strong morning routine.

Regularly leave your comfort zone.

Succeeding at easy tasks doesn’t increase your self-efficacy. Rather, it is when you succeed at challenging tasks that you feel more capable. Self-efficacy increases the most after we struggle with something, make mistakes, fall on our faces, and then get up, figure it out, and succeed.

At first, you won’t feel like you can handle anything outside your comfort zone, but if you get enough reference experiences in which you leave your comfort zone and do just fine, you’ll start to become more confident stepping out it. Plus, you start to become confident doing things you previously felt nervous about. If you leave your comfort zone in a wide variety of ways and on a regular basis, your comfort zone will expand.

Take on responsibilities.

Taking on more responsibilities might be one way to leave your comfort zone. Taking on a new responsibility increases your self-efficacy partly because it makes you more responsible, in the conventional sense of the word: It forces you to be organized, effective, and reliable.

But it also makes you more “response-able,” in the Stephen Covey sense of the word: It makes you better prepared to respond to situations in helpful ways.8 Here’s self-efficacy pioneer Nathaniel Branden articulating the appropriate mindset:

“I am responsible for my choices and actions. To be ‘responsible’ in this context means responsible not as the recipient of moral blame or guilt, but responsible as the chief causal agent in my life and behavior.”9

Pursue goals.

The pursuit and achievement of goals is a critical way to develop greater general self-efficacy. Partly, this is because the achievement itself proves to us that we’re capable. But also because “the process of achieving is the means by which we develop our effectiveness, our competence at living.”9

It is the experiences you acquire and the skills you develop along the way to a goal, more than achieving the goal itself, that create self-efficacy.

Learn how to learn.

Since general self-efficacy is largely about what you think you can handle in the long run, developing your ability to learn is critical. If you’re confident in your ability to figure things out and form lasting memories, you’ll be much more comfortable being a beginner because you’ll know how to improve.

Becoming better at learning is the primary topic of my other blog, so head on over to Northwest Educational Services if you’re interested.

Develop your willpower.

“No one can feel competent to cope with the challenges of life who is without the capacity for self-discipline. Self-discipline requires the ability to defer immediate gratification in the service of a remote goal. This is the ability to project consequences into the future—to think, plan, and live long-range.” –Nathaniel, Branden9

The hardest things we face in life are often those that require the most willpower, so developing greater willpower and being strategic about willpower use are critical components of general self-efficacy. Ditto for dealing with willpower failures well.

“I don’t have self-control” is a classic low self-efficacy statement. It is also a limiting belief. The best way to disprove this false belief is to address your most significant bad habit. If you do the hard work to change the most important and difficult thing you need to change, you’ll see yourself in a new light. You’ll see yourself as a more capable, more powerful person.

Develop your executive function.

Executive function refers to your ability to organize and manage your life. It is actually a constellation of interrelated skills, so there are many different things you can do to improve your executive function. Click here for an in-depth look.

Practice mindfulness.

Mindfulness practices increase how effectively you’re able to respond to the world, rather than merely react to it. Effective responses require time to think, so you need to cultivate a gap between stimulus and response. Exercises that relax and slow you down, such as meditation, “increase the likelihood of more adaptive, self-efficacious thinking.”3 The practice of taking microbreaks can also help with this.

Furthermore, an inability to focus would make anyone feel ineffective, so training the mind to focus through meditation is an excellent way to increase self-efficacy. Mindfulness also enhances your awareness of the present moment, prevents your thoughts and emotions from being controlled by what is happening around you, and gives you greater free will. All these things make you feel more confident.

Remember that you can build momentum.

Developing general self-efficacy is a long game. It requires persistently taking action toward greater skills and regularly challenging yourself to do just a bit more today than you could yesterday.

But if you’re starting from very low self-efficacy, it can be very difficult to even begin this process, so it’s important to keep in mind that it will get easier because you can build momentum. “We know that as people start to build a track record of small successes by solving problems, self-efficacy follows naturally.”2

Taking even a single step in the right direction can kick-start a positive feedback loop that leads to greater motivation and greater confidence. Trust that this is possible, take action, and you’ll soon begin to trust in yourself.

1 Ben-Shahar, Tal. Psychology 1504: Positive Psychology. Harvard Open Course, 2009.

2 Reivich, Karen and Andrew Shatté. The Resilience Factor: 7 Keys to Finding Your Inner Strength and Overcoming Life’s Hurdles. Harmony, 2003.

3 Snyder, C. R., et. al. Positive Psychology: The Scientific and Practical Exploration of Human Strengths. 2nd Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc., 2011.

4 McGonigal, Kelly. The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It. Avery, 2015.

5 Robbins, Anthony. Awaken the Giant Within: How to Take Immediate Control of Your Mental, Emotional, Physical and Financial Destiny! Free Press, 1992.

6 Dweck, Carol. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Ballantine Books, 2007.

7 Neff, Kristin, Ph.D. Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. William Morrow, 2011.

8 Covey, Stephen R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Fireside, 1990.

9 Branden, Nathaniel. The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem: The Definitive Work on Self-Esteem by the Leading Pioneer in the Field. Bantam, 1995.