What are feelings?

What is pain, pleasure, hot, cold, an itch, or a tickle? On a purely physical level, feelings are just nerve signals – neurons firing in your body to communicate with your brain.

What about feelings within your brain? Fear, confidence, sadness, happiness, and the like? These are just nerve signals too – patterns of neurons firing in your brain.

Nerve signals are neutral.

There is nothing inherently good or bad about any nerve signal.

An electrochemical impulse traveling around your body and brain is value-neutral. It is merely a physical phenomenon, akin to photosynthesis, erosion, or snow. These things are not inherently good or bad; they just are.

All feelings are neutral.

Since feelings are nerve signals, and nerve signals are neutral, feelings are value-neutral as well. It’s our interpretation of them that gives them a positive or negative meaning.

We’re accustomed to thinking certain feelings are “bad” and others are “good” because we’ve developed default interpretations for things like pain and pleasure.

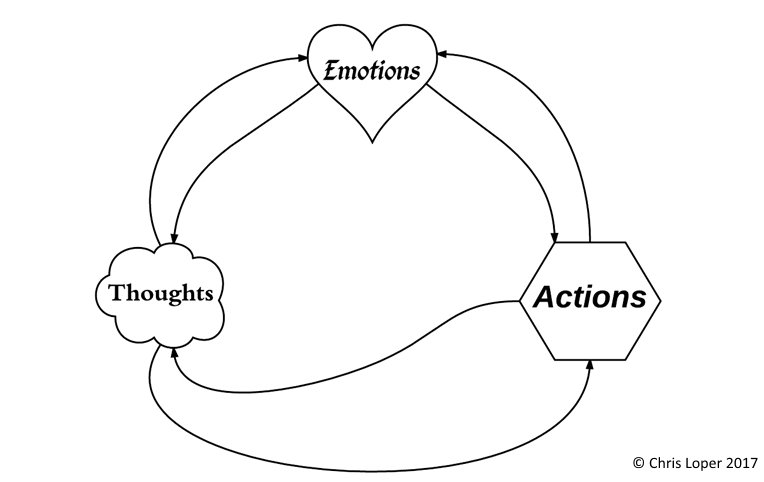

And since that’s the case, we can learn better interpretations that in turn lead to better thoughts, actions, and emotions.

Pain and Discomfort

I have chronic foot inflammation that is generally uncomfortable and sometimes painful.

I usually interpret this feeling negatively, but if I remember that it’s just a nerve signal, I can shift that interpretation to be neutral. It’s not bad that my feet feel this way. It’s just a sensation – neither good nor bad. And on rare occasions, I’ve even been able to find things I like about it. “I kind of like this feeling. It’s familiar. And it’s a little like being in a hot tub.”

Speaking of hot tubs, that’s actually a great example of the neutrality of nerve signals.

When you first get into a hot tub, the hot water on your cold skin is a little bit painful. But during those first few moments while your skin is adjusting, you’re probably not frowning or complaining about the discomfort. In fact, you’re probably smiling because you’ve interpreted the sensation – based on the context – as good.

Even extreme pain, such as from a broken bone, can be understood as good. It’s a nerve signal telling you that you’re hurt and need help. It’s very unpleasant, but it’s also helpful.

Pleasure

Pleasure has a positive default interpretation, but that’s not always wise. If the pleasure is coming from heroin, it’s obviously not a good thing – it comes at too high a cost.

For a more common example, take the pleasure from coming eating a third donut. While that donut might be delicious, there are reasons to see this pleasure as not good: spiking your blood sugar, weight gain, etc.

Here, the game is less about reinterpreting the feeling in the moment and more about reinterpreting our prediction of the feeling.

When contemplating whether or not to eat that third donut, it will help to remember that pleasure isn’t necessarily or wholly good. You can remember that you have competing wants and choose more wisely.

Hunger

Hunger is normally interpreted as a negative feeling, but it’s just a signal indicating that you haven’t eaten in a while.

When I’m fasting, I interpret hunger as a good feeling because it indicates that I’m doing what I set out to do. It doesn’t mean I need to rush to the kitchen and shove food down my throat. It means my body is figuring out that it needs to start burning fat for fuel.

Boredom

Boredom is usually experienced as a bad feeling, but you can learn to interpret it as good.

Boredom is an opportunity to rest your brain, process your feelings, and consolidate the memory of what you’ve been learning. It’s not a feeling to be avoided or alleviated with entertaining distractions. It’s a natural and beneficial state of mind.

Meaningful vs. Meaningless Nerve Signals

The feelings we have can be sorted into two broad categories: meaningful and meaningless.

Not everything we feel has a meaning. Sometimes, they’re just random nerve-firings.

It’s July. You’re sitting by a lake in the mountains, enjoying the sunshine and the beautiful view. You feel a tickle on your left forearm. You look down at it, see that a mosquito has landed on your arm, swat it, and go back to enjoying the scenery.

That was a meaningful nerve signal.

It’s February. You’re sitting on your couch, wrapped in a blanket, reading a novel. You feel a tickle on your left forearm, but there’s no apparent cause. Your arm is covered by a long-sleeve shirt, and nothing about it has changed.

That was a meaningless nerve signal.

My knee hurts. It hurts because I skied hard yesterday. It hurts because my hip is tired, so I’m not walking properly. It hurts because there’s an old injury that I need to be mindful of.

This is a meaningful nerve signal.

My foot hurts. It hurts because my nerves are misfiring. It hurts because my body thinks I’m injured, even though MRIs show that I’m not.

This is a meaningless nerve signal.

Evolution programmed us to be oversensitive and overreactive. Better to feel a tickle on your arm when there is nothing there than to ignore a tickle on your arm when there’s a poisonous spider or malarial mosquito. Better to overly cautious and react with aversion to pain than to recklessly push through the pain and get seriously hurt.

This means we’re inclined to misinterpret meaningless nerve signals as meaningful. Getting it right requires being aware of our tendency to overreact.

Actionable vs. Non-Actionable Nerve Signals

Our feelings can also be sorted into two other categories: actionable and non-actionable.

Just because a signal is meaningful doesn’t mean we have to do something in response to it. But if a meaningful signal does indicate an appropriate response, we’d be wise to obey that command.

If my back hurts, it probably means that I’ve been sitting too long, I need to improve my posture, or I should get on the floor and do some Mackenzie exercises.

Sometimes, though, discomfort isn’t a sign to take action. If I feel hungry while I’m fasting, it’s not a sign that I should eat. If I’m sore from yesterday’s workout, there’s nothing to do but wait.

Numbing

A common response to pain – both physical and emotional – is to numb it with medicine, alcohol, or other drugs.

I could take measures to numb the pain in my knee, but that would be a mistake since it’s a meaningful signal. I need to know when my knee hurts because it’s a critical indicator. If I numbed it, I would push past the point of fatigue and make the injury worse.

I do, however, take measures to numb the pain in my foot because it’s a meaningless signal. Sometimes it hurts for no reason, so numbing it just makes my experience better.

In my late 20s, I was severely depressed, and I “dealt” with this emotional pain by getting high. But numbing myself was unwise because my unhappiness was a meaningful signal. My life had many problems, and I got high to avoid facing them. After I got sober, I was forced to fully feel how bad things were. Only then did I find the motivation to do the hard work of making my life better.

Acceptance

A better option than numbing is acceptance. Because suffering = pain X resistance, accepting unpleasant feelings reduces the suffering they cause us.

Let’s go back to my knee pain for a minute.

Although it is a useful signal, it would be very easy to interpret it negatively, seeing the pain as bad and getting upset about it. Sometimes, this is exactly what I do.

But when I’m being mindful of how I interpret the signal, I recall that my knee injury came from a terrible ski fall that should have killed me, and instead of getting upset, I feel lucky to be alive.

Every unpleasant feeling can be embraced in this way, or at least accepted.

Feelings are just nerve signals, after all.

You get to assign the meaning.