“The pain that’s created by avoiding hard work is actually much worse than any pain created from the actual work itself.” –Russel Simmons1

Procrastinating comes with many costs.

One is “the thinking cost” – the taxing mental exercise of thinking about whatever you’re not doing, coming up with excuses to not do it, and then feeling guilty about procrastinating as you choose a more pleasant task. The longer you put something off, the more times you pay the thinking cost of procrastination.

Another is stress. This is both a cause and a consequence of procrastination. We tend to avoid stressful tasks, putting them off for the future in order to feel better.2 But feeling better is short-lived because the next time we think about the task, the deadline is even closer, so we feel even more stressed.

Procrastination is similarly intertwined with anxiety. If you feel anxious about a task because you don’t think you can do it well, you’ll be inclined to put it off. Avoiding the work might provide short-term relief, but the anxiety will come back stronger later.

These are all just manifestations of the pain of procrastination.

Procrastination is painful.

The more averse we are to a task, the more likely we are to procrastinate.3 And this aversion actually manifests as psychological discomfort – a type of pain – that can be seen in fMRI scans, as Dr. Barbara Oakley explains in A Mind for Numbers:

“We procrastinate about things that make us feel uncomfortable. Medical imaging studies have shown that mathphobes, for example, appear to avoid math because even just thinking about it seems to hurt. The pain centers of their brains light up when they contemplate working on math.”4

So your brain experiences thinking about an unpleasant task in much the same way that it experiences something physically painful. And just as you naturally pull your hand back from a hot stove, you avoid tasks that trigger this kind of psychological pain.

Beating Procrastination

Now here’s the kicker – the pain of procrastination is nearly all in the anticipation, not in the task itself. When you begin doing the work, activation in the pain center of your brain dies down after about five minutes.4

We experience this relief as thoughts and feelings like, “Oh, it’s not as bad as I thought, or “I’m actually glad I’m getting this done right now.”

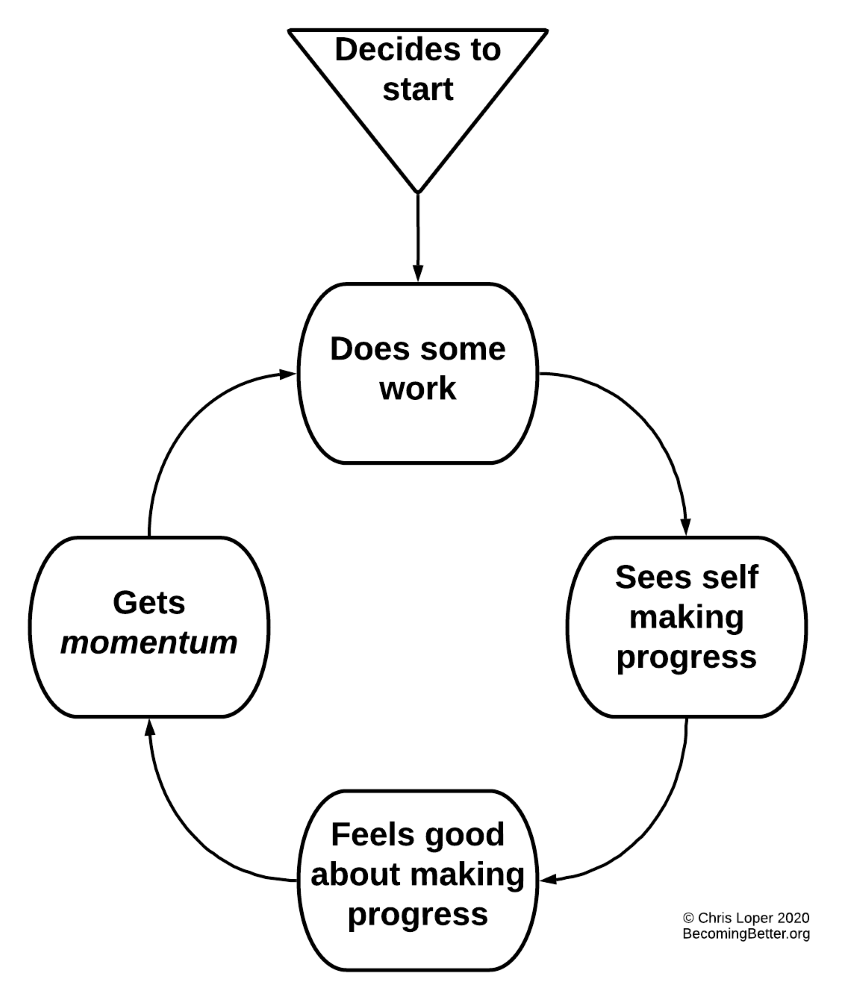

It was actually research like this that led to the invention of the 5-minute takeoff strategy, where you commit to doing five minutes of work in the hopes that you’ll build momentum and want to continue.

And studies like this show that we have the power to reduce the amount of suffering that we experience from unpleasant work. We can’t make the task become smaller or easier by putting it off, but we can eliminate the pain of procrastination by getting it done now:

- If you’re tormented by thinking about a big project, you’ll feel better if you get started.

- If you’re stressed out by a task, you might as well just get it over with.

- If you’re feeling anxious about the work you have to do, the only cure is to do the work.

You and Your Future Selves

We procrastinate more when we imagine our future selves to be strangers:5

I don’t feel like doing this now, so I’ll make Future Chris do it.

But then, Future Chris turns out to be me.

So one way to overcome procrastination is to remember that your future selves are you. The work you’re trying to avoid won’t be done by some stranger; it’ll be done by you.

And by putting it off, you’re not saving yourself any pain. You’ll still have to do the work, and it won’t be any less uncomfortable than it would be right now.

Plus, you’re needlessly causing yourself extra pain – the pain of procrastination.

1 Simmons, Russel. Do You!: 12 Laws to Access the Power in You to Achieve Happiness and Success. Gotham, 2007.

2 Lieberman, Charlotte. “Why You Procrastinate (It Has Nothing to Do With Self-Control).” The New York Times. March 25, 2019.

3 Zhang, Shunmin, et al. “To do it now or later: The cognitive mechanisms and neural substrates underlying procrastination.” Wires Cognitive Science. 14 January 2019.

4 Oakley, Barbara. A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra). Penguin, 2014.

5 Eve-Marie C. Blouin-Hudon, and Timothy A. Pychyl. “Experiencing the temporally extended self: Initial support for the role of affective states, vivid mental imagery, and future self-continuity in the prediction of academic procrastination.” Personality and Individual Differences. Volume 86, November 2015, Pages 50-56.