Meditation is a collection of paradoxes.

It is simultaneously the simplest thing to do and the hardest thing to do. It involves sitting and doing nothing, but it requires great effort. It relaxes the mind but also gives it a workout. And you benefit the most from meditation when you’re really bad at it.

Let’s unwrap these paradoxes and get you set up to develop a consistent meditation practice.

But why would you want to become a meditator? Because meditation is the primary way to cultivate mindfulness.

My last post discussed mindfulness in depth, so if you missed that, click here to get caught up. And if you’re short on time (or in need of a review), here’s a quick recap:

- Mindfulness has numerous benefits that have been demonstrated scientifically ranging from improved physical health to enhanced cognitive ability to increased happiness.1

- Mindfulness is a collection of four interrelated skills: presence, curiosity, acceptance, and non-attachment.

- Working together as a whole, these four components can produce profound benefits: greater mental health, free will, and wisdom.

It is not enough to know what mindfulness is. One must practice. And meditation is the best way to deliberately and methodically practice mindfulness.

There are many different types of mindfulness practices and meditations. Some involve movement, like walking meditation and yoga. Some involve working through a particular series of thoughts, like loving-kindness meditation. I will focus on the simplest and most common form of practice: breathing meditation.

As I said, breathing meditation is very simple. There is only one thing to do:

Focus on your breath.

That’s it. You breathe in, and you breathe out, and you make an effort to focus on the sensation of breathing. You don’t have to force yourself to breathe in any particular way. You don’t have to shut your mind off from thinking. And you don’t have to sit cross-legged on the floor.

Most people do it sitting, but some people do it laying down, and you could even do it standing up if you wanted. If you do choose to sit, as I do, just sit in any way you find comfortable, whether that’s in an office chair, on the couch, or on a park bench – wherever you want. You’re welcome to sit on a cushion on the floor yogi-style, but that’s not necessary. The only strong recommendation I have about how to sit comes from Jon Kabat-Zinn who advises us to “sit with dignity,”2 which basically means don’t slouch. You can do whatever you like with your hands. I just fold them in my lap.

The other physical element that’s commonly a part of the practice is closing your eyes. This is simply to help you focus on your breath by shutting out visual stimuli that might distract you. But you can meditate with your eyes open if you like. Some people like to stare at a wall or stare at some natural scenery while they meditate. It’s up to you.

Likewise, it’s easier to meditate somewhere quiet. Noise is generally distracting, which makes it harder to focus your attention on your breath. But it is absolutely possible to meditate in a noisy environment, just as it is possible to ride your bike into a headwind. The added difficulty might even make it a better mental workout. Some people also like to listen to calm, instrumental music while they meditate. Last month when I was in Hawaii, I meditated on the beach each morning to the rhythmic sound of waves crashing on the shore.

Now you try.

Regardless of where you are right now, please take one minute (you might set a timer) to try this process. The rest of this article will be much more meaningful to you if you spend a minute trying to focus on your breath. Seriously, do it now.

Okay, now that you’ve done tried breathing meditation, you know how hard it is. But don’t be discouraged.

Struggling is the whole point.

If meditation were easy, it wouldn’t be beneficial. The simple task of focusing on your breath is shockingly difficult. But that’s actually a good thing. Struggling is the whole point. Let me explain.

When you begin your meditation session, you take a breath and you direct your attention to the sensation of breathing. Within one or two breaths – and often before the first exhale is complete – your mind will wander off.

You’ll start thinking about what you have to do tomorrow. Or you’ll replay something that happened earlier in the day. Or you’ll wonder what’s going to happen next in Game of Thrones. Or you’ll realize that you feel hungry. Or your attention will be drawn to that itch on your leg (it’s okay to scratch it by the way). Or you’ll start daydreaming.

All of this is normal, natural, and completely okay. Such mental wanderings are inevitable. No one, and I mean no one, can shut this off. Very serious, long-term practitioners of meditation can quiet their minds very well and pause these mental wanderings for various lengths of time, but they never fully go away.

So please don’t fall into the most common meditation pitfall: the misconception that you have to stop your thinking, and that if you can’t stop your thoughts, you can’t meditate.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The art and practice of meditation is recognizing when your mind has wandered off and choosing to bring your attention back to your breath. It is this repetition of recognizing and choosing that develops the mind.

“I am always amused when people interpret the fact that they are chasing their mind all the time as an indication that they are not good at meditation. What they are missing, and this is very significant, is that they wouldn’t be chasing their mind and bringing it back to task if they weren’t noticing that their mind was running off! I have commented many times that what many people interpret as a bad meditation is a really good one, if not a great one, because they are getting many opportunities to pull their mind back.” –Thomas M. Sterner3

In a ten-minute meditation session, I might catch my mind wandering off a few dozen times, each time deliberately returning my focus to the sensation of breathing. And my attention will stay on my breath for a moment or even for a few breaths, but then it will wander off again.

This rhythm of bringing your attention to your breath, finding that it has wandered off, and deliberately bringing it back is akin to lifting weights. You lift the weight up, gravity naturally pulls it back down, and then you lift it up again. If it were easy – if you were lifting Styrofoam weights – you wouldn’t get any stronger. The benefit comes from the struggle.

Mental Training

This metaphor actually has some resonance in physical reality.

The act of deliberate focus is performed by the prefrontal cortex, which, in long-term meditators shows greater neural density.4 In addition to focusing our attention, the prefrontal cortex is responsible for planning, strategizing, and organizing; it’s like the CEO of the mind.5 This very practical benefit is one reason meditation has become so popular in the business world.6

Mindfulness practices also strengthen the connection between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex.7 This may sound esoteric, but it’s actually very important. Strengthening this connection reduces the likelihood of an emotional meltdown. Why? Because when the prefrontal cortex is aware of what’s happening in the amygdala, it can prevent what’s known as “amygdala hijack” – a state in which negative emotions like fear, sadness, and anger take control of the brain and our behavior.8

These physical changes are manifestations of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which I often simply as “The brain is like a bunch of muscles.” We might think of mindfulness as “psychological fitness” akin to physical fitness. Sitting down for meditation is like going to the mental gym. And, as with physical exercise, it’s well worth the effort.

We don’t meditate to experience transcendence during the practice or to have any other emotional experience while sitting and breathing. Rather, we meditate in order to think, feel, and act better during the rest of our lives. Meditation helps with day-to-day living and moment-to-moment emotional regulation. You may or may not enjoy the practice, and that is irrelevant. The benefits are experienced outside of the practice, when you’re out in the world, interacting with other people, or dealing with personal challenges. Just as one does not do pushups in order to become good at doing pushups – you do pushups to become stronger – we’re not trying to get “good” at meditating; we’re trying to get good at life. It’s about functional strength.

“Your mind is the basis of everything that you experience and of every contribution you make to the lives of others. Given this fact, it makes sense to train it.” –Sam Harris9

Gentleness

As much as I like the gym metaphor, please don’t take it too far. The old work-out mantra, “No pain, no gain,” isn’t appropriate here. It is essential that you approach meditation with gentleness and self-compassion.

“You can’t develop mindfulness by force. Active teeth-gritting willpower won’t do you any good at all. … This does not mean that mindfulness happens all by itself. Far from it. Energy is required. Effort is required. But this effort is different from force. Mindfulness is cultivated by a gentle effort. You cultivate mindfulness by constantly reminding yourself in a gentle way to maintain your awareness of whatever is happening right now.” –Bhante Gunaratana10

Struggling painfully to maintain focus is not the goal and neither is fighting whatever your mind brings up. Remember, one of the key aspects of mindfulness is acceptance. It’s okay to just sit and observe the thoughts and feelings that your mind produces without stressing out about whether or not you’re doing a good job focusing on your breath.

“Even after long practice, you find yourself suddenly waking up, realizing you have been off the track for some while. Don’t get discouraged. Realize that you have been off the track for such and such a length of time and go back to the breath. There is no need for any negative reaction at all. The very act of realizing that you have been off the track is an active awareness. It is an exercise of pure mindfulness all by itself.” –Bhante Gunaratana10

Learning to quiet and focus your mind takes a very long time, and this is perfectly okay. Eknath Easwaran explains that the mind “never rests . . . it goes here, there, ceaselessly moving through sensations, images, thoughts, hopes, regrets, impulses. Occasionally it does solve a problem or make necessary plans, but most of the time it wanders at large, simply because we do not know how to keep it quiet or profitably engaged.”11

If you don’t give yourself permission to be human, you’ll probably find meditation rather unpleasant.

My favorite antidote to the tendency to be harsh with yourself during a meditation practice is the puppy metaphor, which I learned from a free online mindfulness course offered for free by Monash University.

Here it is:

Your mind is like cute, little puppy whom you’re trying to train. You’d like the puppy to learn how to lay down on a rug in the middle of the living room and stay there, so you gently carry the puppy to the rug, set him down, and calmly ask him to stay. (This is you, bringing your attention to your breath.) But, because he’s an energetic little puppy, he immediately gets up and bounds off toward whatever catches his interest. (This is your mind wandering off.) Unsurprised, you calmly go find the puppy, bring him back to the rug in the middle of the living room, and gently set him down. (This is you returning your attention to your breath.)12

Would you get angry at a puppy for running off? Would you yell at him for being unfocused? Would you decide that you don’t like the puppy because he won’t stay put? Of course not. So please be as gentle with your mind as you would be with a puppy.

Here are some other popular metaphors that can help with the meditation process:

- Imagine yourself as a mountain. The thoughts and feelings that arise in your mind are just clouds floating by the mountain. You see them, they may even rain on you for a time, but they eventually pass by.

- Imagine your mind is a stream of thoughts and feelings. Your job is to sit on the bank of the stream and observe them. Occasionally you get sucked into the stream and carried along by your thoughts and feelings for a while. But then you notice what has happened and pull yourself out.

- Imagine being in the ocean. Your thoughts and feelings are waves on the surface, but you sink into the calm depths. From the serenity of the depths, you can look up at the chaos on the surface and be undisturbed by it.

Tips for Beginners

Here are some ideas to make meditation easier.

#1 Take slow, deep breaths.

When you’re trying to take slow, deep breaths, you naturally bring your attention to the process of breathing, which is the thing you’re trying to do in meditation anyway. So I usually start my meditation with a few deliberately slow, deep breaths, and, whenever I find my mind has wandered off, I’ll use a slow, deep breath to help bring it back.

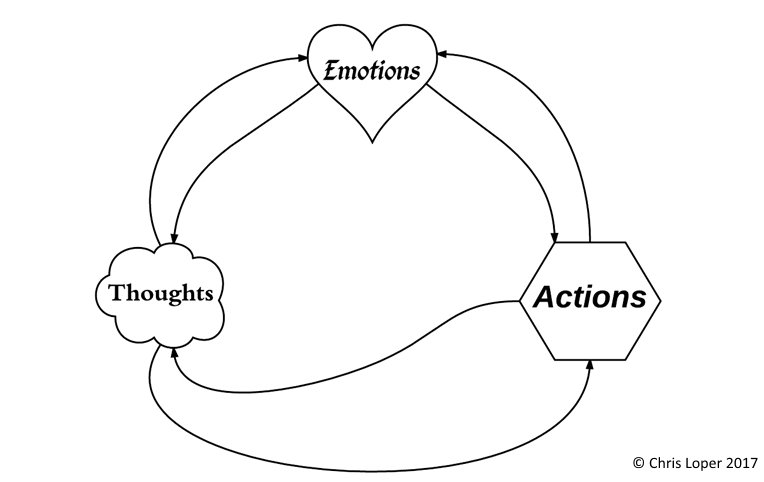

Slow, deep breaths are also helpful because they facilitate relaxation. Meditation and mindfulness, in general, are easier when we’re relaxed. Why do slow, deep breaths help you relax? Because of self-perception. Your mind observes what your body is doing and aligns your thoughts and feelings with your behavior. Since slow, deep breaths are a relaxed behavior, they trigger relaxation in the mind.

And this isn’t just some hypothesis about mind-body connection, it is literally what happens within the nervous system. Slow, deep breathing techniques “stimulate the vagus nerves, the main pathways of the parasympathetic nervous systems. These pathways ascend to relay stations in the brainstem and extend via the thalamus to the cerebral cortex, where they quiet the excess thinking activity. At the same time, other branches of the pathway enter the centers of emotion regulation in the prefrontal cortex and in the limbic system, including the amygdala and hippocampus, where they help reduce anxiety and emotional overreactivity.”13 In other words, “Messages from the respiratory system have rapid, powerful effects on major brain centers involved in thought, emotion, and behavior.”13

#2 Breathe through your nose.

This has a similar effect. The nasal cavities release nitric oxide, so nose breathing brings more nitric oxide into the lungs.14 This opens the blood vessels in the lungs, making them more receptive to oxygen, and it also helps lower blood pressure.14 This creates a physiological calm that, through self-perception, facilitates a psychological calm.

#3 Count your breaths.

Counting your breaths as you take them helps you stay focused on your breathing. Don’t worry if you lose count. You can start over as many times as you need to.

#4 Set a timer.

As a beginner, I don’t recommend sitting down for an open-ended meditation session. You’ll probably find yourself wondering how long it has been and whether or not you should stop yet. Set a timer that has a friendly, non-abrasive alarm sound, so you can just sit and meditate without concern for the length of time that has passed.

#5 Start small.

I also don’t recommend that beginners sit down for lengthy meditations. Many resources recommend 20 minutes of daily meditation, but this is probably way too much for beginners. Remember, it’s like mental exercise, so if you’ve never done it before, you’re probably out of shape. No doctor would tell someone who never exercises to go run ten miles. The same principle applies here. Start small. My own practice began with three minutes of daily meditation.

#6 Use guided meditations.

Many people, especially beginners, like to use guided meditations. These are audio recordings that offer up some simple instructions and gentle reminders during your practice to help you stay on track. These make meditation easier, and they also serve as a timer. There are a wide variety of guided meditations online and on YouTube, as well as numerous smartphone apps. The ocean metaphor described earlier comes from Eckhart Tolle. (Search YouTube for “Eckhart Tolle guided meditation, and choose one that’s about 11 minutes long. It’s my favorite guided meditation.)

Patience

While meditation brings many benefits ranging from increased intelligence to greater happiness to improved physical health,1 in my own experience, the most obvious benefit of meditation has been an increase in patience. In the two and a half years I’ve been meditating regularly, I’ve become a much more patient person.

Waiting in line, being stuck in traffic, and being bored are no longer annoying or frustrating. I’m much more content with doing nothing than I used to be, and the reason is obvious – I’ve been practicing. Furthermore, moments and minutes when I have to wait have been transformed from inconveniences into opportunities to meditate – OTMs.

While meditation does cultivate patience, we must also bring a certain level of patience to the practice itself. The benefits of meditation are sometimes noticed immediately, but for the most part, results come later. I didn’t realize how patient I had become until about a year into my practice, though I was surely improving the whole time. There is no way to transform your mind overnight, but you can improve enormously in the long run if you keep your eyes on the process.

“This is not a race. You are not in competition with anybody, and there is no schedule.” –Bhante Gunaratana10

To make progress with your meditation, and to turn it into an automatic habit, consistency is key. This is another reason to start small. It’s hard to say you don’t have time for three minutes of meditation each day.

It also helps to track your effort and rely on reminders, not memory. The tool that got me to meditate regularly was a calendar chain.

“The key to reaping the rewards of meditation is to develop a regular, daily practice, no matter how brief. How about making a personal commitment never to go to sleep without having meditated that day, even if just for one minute?” –Rick Hanson, Ph.D.15

Think of meditation as just another basic, daily health practice like brushing your teeth, eating vegetables, and exercising. It’s something we all ought to do every day. You probably don’t worry that you’re doing a bad job brushing your teeth – you just do it. Likewise, “There is only one failure in meditation: the failure to meditate faithfully.”11

And “Consider the final words the Buddha spoke to his disciples. … ‘Just do your best.’” 16

1 Williams, Mark, and Danny Penman. Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World. Rodale, 2011.

2 Kabat-Zinn, Jon. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. Hachette Books, 2005.

3 Sterner, Thomas M. Fully Engaged: Using the Practicing Mind in Daily Life. New World Library, 2016.

4 Lazar, Sara W., et al. “Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness.” NIH Public Access. US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. February 6, 2006.

5 MacDonald, Matthew. Your Brain: The Missing Manual. O’Reilly Media, 2008.

6 Denning, Stephanie. “The Benefits Of Meditation In Business.” Forbes. February 2, 2018.

7 Davidson, Richard J., Ph.D. and Sharon Begley. The Emotional Life of Your Brain: How Its Unique Patterns Affect the Way You Think, Feel, and Live—and How You Can Change Them. Plume, 2012.

8 Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books, 2005.

9 Harris, Sam. Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion. Simon & Schuster, 2014.

10 Gunaratana, Bhante. Mindfulness in Plain English. Wisdom Publications, 2011.

11 Easwaran, Eknath. Passage Meditation: Bringing the Deep Wisdom of the Heart into Daily Life. Nilgiri Press, 2008.

12 “Mindfulness for Wellbeing and Peak Performance.” Monash University.

13 Brown, Richard P. and Patricia L. Gerbarg. The Healing Power of the Breath: Simple Techniques to Reduce Stress and Anxiety, Enhance Concentration, and Balance Your Emotions. Shambhala, 2012.

14 McKeown, Patrick. The Oxygen Advantage: Simple, Scientifically Proven Breathing Techniques to Help You Become Healthier, Slimmer, Faster, and Fitter. William Morrow, 2015.

15 Hanson, Rick, Ph.D., with Richard Mendius, MD. Buddha’s Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & Wisdom. New Harbinger Publications, Inc., 2009.

16 Millman, Dan. The Way of the Peaceful Warrior. H.J. Kramer, 2006.