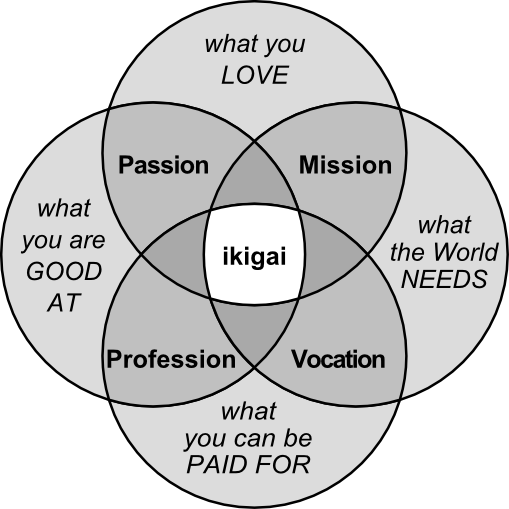

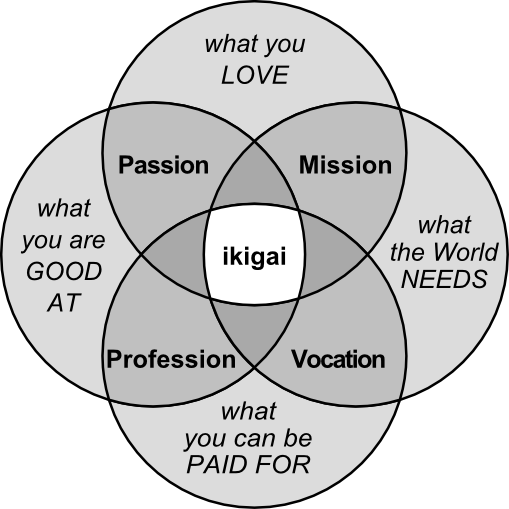

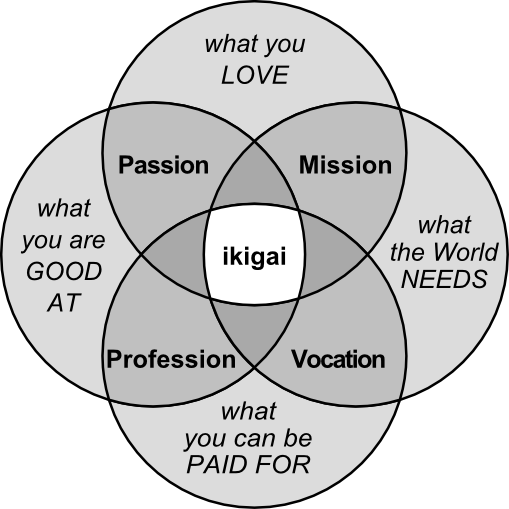

In Japanese culture, there is this concept called “ikigai,” which loosely translates as “the reason why you get up in the morning.” Every person, it is believed, has an ikigai that they must search for. The search is long and deeply personal, but once your ikigai is found, it is what you devote your life to. It is your calling, your one true purpose.

At first glance, you might think this is another one of those ideas that sounds nice, but isn’t really true. And you’d be right. Plus, this Venn diagram model of ikigai is a westernized misinterpretation of the actual Japanese concept.* But there are some very important lessons to be gleaned from the ikigai diagram, so let’s not throw it out just yet.

Basically, I see this concept as an unrealistic ideal. It’s very rare to find a true ikigai – a single activity that satisfies all the circles. And a person who really believes in ikigai might waste his whole life searching for it, wrongly thinking that if he can’t find it, he can’t live a meaningful, happy life.

The truth is we don’t need to find one thing. We can find deep satisfaction through several activities; we can approach this thing from multiple angles. Also, searching for your ikigai is the wrong approach, as I’ll explain shortly.

Those criticisms aside, I love this diagram:

The ikigai Venn diagram provides a powerful framework for thinking about how to spend your time. The most important lessons are as follows:

- Don’t neglect any of the circles.

- Aim for the intersections.

Balance

Lesson #1 is really about balance. Ignoring one or more of the circles is a recipe for dissatisfaction.

If you focus only on one of the circles, your life will be way out of balance. The most classic example is a workaholic businessman who only works for money, never enjoys himself, never gets to use his signature strengths at work, and never contributes to his community. Such a person may appear outwardly successful, but will probably be deeply unhappy.

And even if you satisfy three of the circles and ignore the fourth, you’ll still feel like something’s missing. Perhaps you have a career you love that you’re quite good at, but your job doesn’t provide anything the world truly needs. Volunteering or finding another way to give back would almost certainly fill a psychological void.

Overlap is good.

Lesson #2 is that you’d be wise to aim for the intersections of the circles. Whenever possible, you should move closer to the center. Time spent at the intersections of these circles is time well spent.

For example, if your job is also something you’re also good at, you’ll find much more satisfaction at work. Or if you become more skilled at something you love to do, you’ll enjoy it even more. Or you can take something you do for fun, such as playing baseball, and use that as a way to contribute to your community, by, say, volunteering to coach your neighborhood’s little league team. And if you have the choice between two jobs that both pay the bills, and one serves an important need while the other does not, you should probably choose the job that lets you help others on a daily basis.

While few people find a true ikigai, most people discover a few things that are almost ikigai, things that are at the intersection of two or three circles. And these, I believe, are good enough.

Three Classic Mistakes

The ikigai diagram also reveals what’s wrong with these three classic mistakes:

- Spending too much time on just one thing.

- Spending your time on too many things.

- Doing too little.

Spending too much time on just one thing is risky. You could become amazingly skilled at that one thing, but you’re putting all your eggs in one basket. If that one thing is pursuing the art form you love, you might never make a career out of it. Without a backup plan, you could easily wind up a “starving artist.” If that one thing is your favorite sport, you could become injured and unable to play. Without other ways of enjoying yourself, you could easily wind up depressed. You don’t have to devote your life to just one thing, and it’s probably better not to.

Furthermore, it’s needlessly limiting to believe that your life should have only one purpose. You’ll probably find your life richer and more fulfilling if you devote yourself to multiple passions. And the world may be glad you did. Steve Martin is most well known for being a Hollywood actor, but he began his career as a standup comedian, and he now plays banjo as the leader of Steve Martin And The Steep Canyon Rangers. Or consider Bill Gates, who clearly found his ikigai in computer software development, but now, along with his wife Melinda, runs the world’s largest charity.

On the other hand, spending your time on too many things means that you’ll spread yourself too thin to become highly skilled. You won’t be amazing at anything; you’ll just be mediocre at many things. The Jack of all trades is a master of none, and he probably won’t get paid very well for his work.

But what about being a Renaissance man? Well, the often-idealized Renaissance men, such as Leonardo Da Vinci, became excellent at a handful of things. They had diverse interests, but they spent enough time on a few of them to be memorable. So you can do many things in your life, but remember that you only have time to become really good at a few things. Choose wisely.

Lastly, we have doing too little, which is probably the worst of the three mistakes. This means failing to cultivate any hobbies or passions, doing the bare minimum to make a living, ignoring opportunities to help others, and not developing any new skills. At various times in my life – depressed times – I fell into this lifestyle. Now, if dissatisfaction results from ignoring any one of the circles, you can imagine the despondency that results from ignoring all four.

The best way I know to get out of this sort of funk is to take action, thereby taking the reins of the feedback loop that controls your life. Furthermore, I would recommend starting with the circle on the right and asking, “What does the world need?” and then taking some small action to help. It has been said that it’s hard to be unhappy when you’re being useful.

On that note, if you’re looking for a happier, more satisfying life, leisure is not the answer. In his book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes how his research discovered “the paradox of work”:

“Thus we have a paradoxical situation: On the job people feel skillful and challenged, and therefore feel more happy, strong, creative, and satisfied. In their free time people feel that there is generally not much to do and their skills are not being used, and therefore they tend to feel more sad, weak, dull, and dissatisfied. Yet they would like to work less and spend more time in leisure.”1

Work your way to the center.

Now to address the concept of “searching” for your ikigai. The western equivalent is “finding your passion.” Countless self-help gurus and well-meaning career advisors tell you to first discover and then follow your passion. This advice is wrong on three levels. First, it assumes that everyone has a true calling – a single activity that will satisfy both their financial and psychological needs. Second, it assumes that everyone who discovers their passion will also have the freedom to pursue it. And third, it assumes that your true passion can be discovered through pure introspection.

The reality is that, while there’s a slim chance you’ll discover your ikigai while sitting and thinking about it, it’s much more common to develop your ikigai through hard work. And it might turn out to be something you can get paid for, but maybe not. If you’d like to get paid for something, but the world doesn’t want to pay you to do it, tough luck. Or if you could get paid for doing what you love, but you don’t have the skills, then you’ll have to study and practice your way to employability; you’ll have to earn it. And in the meantime, you’ll need to earn a living through other means, so you’ll only be able to pursue your calling in your spare time.

In other words, having a passionate goal isn’t enough, but if you work hard enough, you might land your dream job. Steve Martin, after he became famous, was sometimes asked by aspiring comics for advice on how to launch their careers. Hoping for inside tips on how to find a good agent, they were instead told to hone their craft through hard work. “Be so good they can’t ignore you,” he told them.2

That Steve Martin story comes from Cal Newport’s excellent book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love. In it, he argues that we should discard the “passion mindset” for a “craftsman mindset.”2 This means we should dedicate ourselves to mastering a craft rather than seeking work we’re passionate about. Then, because we tend to enjoy doing things at which we’re very skilled, we’re likely to become passionate. If we focus on getting really good at our work, we’ll be drawn toward the center of the ikigai diagram.

(See also: 7 Problems With “What Do You Want To Be When You Grow Up?”)

Here’s my own story of working my way to the center:

I’m currently employed as an educator and a writer, and if you travel back in time to my late 20s, you would still find me teaching and writing but with one important difference: I wasn’t getting paid. You see, I’ve always liked to teach and write, but back then, I wasn’t good enough to get paid for either. I was purely in the top circle of the diagram, doing what I loved.

With consistent practice, I improved, and I came to enjoy both writing and teaching more than ever. I took a hobby, worked on becoming good at it, and turned it into a passion. I aimed for an intersection in the diagram and worked my way there.

Continuing to teach and write as a passion, I gained confidence as a teacher and built a portfolio of high-quality writing. Together, these landed me the job I have now: academic coaching and writing the blog for Northwest Educational Services. I worked my way into the intersection between passion and profession.

And, as it turned out, the world needed the work that I do: empowering students and parents with knowledge, skills, and healthy mindsets. Lo and behold, I found myself right in the middle of the diagram; I had an ikigai.

In my 20s, I could have never envisioned the fulfilling career I now enjoy. It would have been impossible to end up where I am today by just sitting around and thinking about what my purpose was, waiting to discover it through introspection. With no clear goal in mind, I aimed for the intersections and worked my way toward the center. I worked my way to an ikigai.

You don’t have to settle for just one.

One way the ikigai diagram can be misleading is that it seems like you only get to have one true calling, but this isn’t the case.

In my early 30s, I studied the science of behavioral change because, quite frankly, I needed to. I was a recovering addict with many bad habits. By adopting healthier mindsets and learning effective strategies, I steadily swapped out my bad habits for good ones and transformed my life. In other words, I became good at behavioral change. Then I started teaching these strategies in my weekly class, and I started teaching them to the students I was working with. People ate it up, and I loved the work. So I launched my habit coaching business and started getting paid to help adults change their lives. Voilà! Another ikigai!

Life is short, so you can’t do everything, but you can pursue multiple passions that align with the world’s needs, and you can become so good at them that you get paid for your work.

Lean into your strengths.

The ikigai diagram also lines up with something many a great teacher has said: It’s better to focus on using your strengths than to focus on correcting your weaknesses.

All of the questions asked by the ikigai diagram are positive ones: What do I enjoy doing? What are my skills? Where can I find a financial opportunity? What can I offer the world?

If your particular strengths cause you to answer two or more of those questions with the same answer, then you’ve found something worth focusing on. Here’s a powerful exercise to help you decide what to do with your time:

- Write down 3-5 answers to each of the circle questions.

- Look for overlap – activities that wound up on more than one list.

- Devote more time to those activities.

Or, if you’re unsure where to begin, start with learning. Take anything that you already do for fun, for work, or out of service to others, and learn more about it. Acquire skills, take classes, read books, and practice. Self-education will pull you toward the “what are you good at?” circle, thereby landing you at an intersection of two or more circles. Build up your strengths and you’ll have more options.

(See also: Increase Happiness By Using Your Signature Strengths)

Mind the foundation.

Lastly, several important things are left out of the ikigai model.

One is social relationships. The pursuit of a fulfilling, joyful life will always be incomplete if it doesn’t include the cultivation of meaningful connections with other people.3 Don’t get so wrapped up in the pursuit of ikigai that you neglect your friends and family.

Likewise, you won’t have the energy to work toward the center if you don’t practice good self-care. That’s why I start every day with a routine of physical and psychological maintenance.

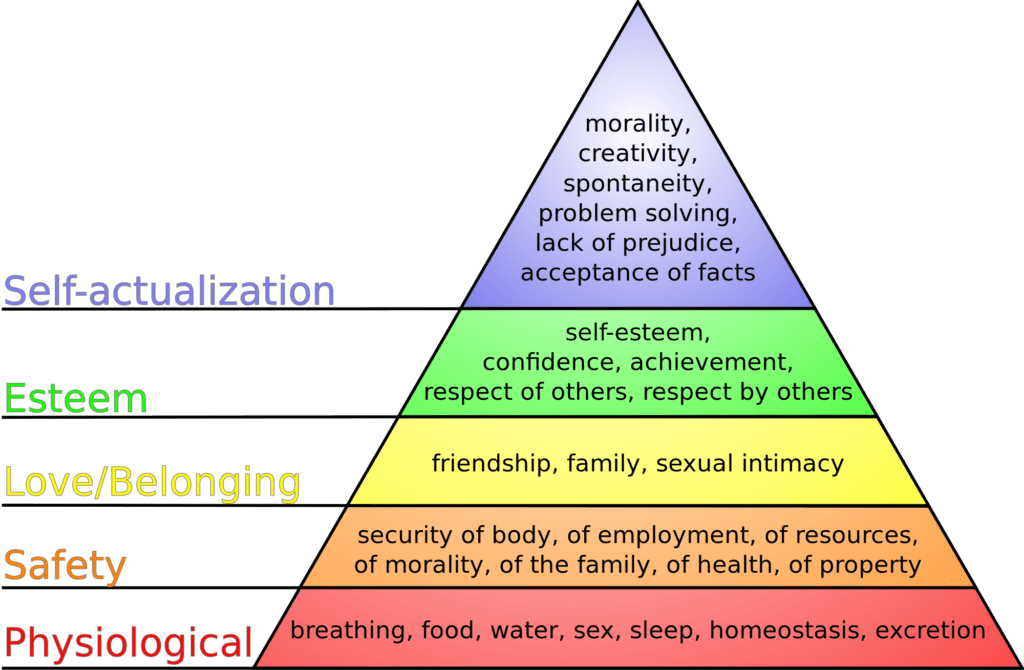

Remember Maslow’s hierarchy of needs?

J. Finkelstein. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.” Wikimedia Commons.

The pursuit of ikigai is really about self-actualizing; it’s about the top of the pyramid. So if you want to satisfy your ikigai circles, you’ll first need to build a strong foundation, and that means establishing healthy habits. If that’s something you’re struggling with, click here to learn about habit coaching and schedule a free consult today.

Realistic Optimism

It’s unrealistic for most people to find a true ikigai, and that’s okay. We need to employ realistic optimism and approach this model from multiple angles. Rather than waiting around to hear a calling from the center, we need to work on multiple paths toward the center.

And it’s okay if you never get there. As long as you’re aiming for the intersections and not neglecting any of the four circles, you’ll be progressing toward greater fulfillment.

*The true Japanese concept of ikigai is less about career and more about the way you live your daily life. It’s less about what you do than how you do things. See “Ikigai Is Not a Venn Diagram” by Nicholas Kemp for details.

1 Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row, 1990.

2 Newport, Cal. So Good They Can’t Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love. Grand Central Publishing, 2012.

3 Newman, Kira M. “Is Social Connection the Best Path to Happiness?” Greater Good Magazine. June 27, 2018.