“Flow is an optimal state of consciousness, a peak state where we both feel our best and perform our best. It is a transformation available to anyone, anywhere, provided that certain initial conditions are met. Everyone from assembly-line workers in Detroit to jazz musicians in Algeria to software designers in Mumbai rely on flow to drive performance and accelerate innovation. And it’s quite a driver. Researchers now believe flow sits at the heart of almost every athletic championship, underpins major scientific breakthroughs, and accounts for significant progress in the arts. … From a quality-of-life perspective, psychologists have found that people who have the most flow in their lives are the happiest people on earth.” –Steven Kotler from The Rise of Superman1

Okay, you’ve got my attention. But what the heck is this “flow” thing?

Flow is a state of mind experienced when you perform an activity that is completely engaging. You become so absorbed in the activity that time passes unnoticed and self-consciousness evaporates. An expert piano player fluidly stroking keys, totally in the moment. A writer pouring her thoughts onto the page. A skier arcing gracefully down the mountain.

When experiencing flow, you are completely focused on the task at hand. The task is not easy, but you are crushing it. You are in the zone.

Not only is flow a state of peak performance, but it’s also a peak experience, emotionally. We love experiencing flow. To say that it makes us happy is both an oversimplification and an understatement. Flow is deeply satisfying in a way that simple pleasures cannot measure up to. Flow is why great artists and athletes and scientists spend long hours on their craft. To outsiders, their efforts may look like work, but they are actually motivated by the profoundly gratifying experience that is flow.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced something like “me-high cheeks-sent-me-high”) is the researcher who pioneered the concept of flow. He is one of the founding fathers of positive psychology and is currently the Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University. Csikszentmihalyi spent many years studying highly creative people and world-class performers in a variety of domains, and he found that the world’s top artists, authors, musicians, scientists, inventors, entrepreneurs, and athletes all routinely experience a state of transcendent absorption while engaging in their craft.2 While they’re in this state, things seem to just smoothly pour out of them, so he called it “flow.”

But flow isn’t something that’s reserved for world-class experts and the highly creative. It’s something anyone can experience. You’ve already experienced it many times in your life, but you could be experiencing it more.

Flow doesn’t happen automatically. It takes a special set of circumstances that you can consciously create. I want to help you understand how flow works because that will allow you to get into flow more often.

Here are the key features of flow, as described by Csikszentmihalyi in his book, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention:

- “There are clear goals every step of the way.” You know what you’re supposed to do.

- “There is immediate feedback to one’s actions.” You know you’re doing it right.

- “There is a balance between challenges and skills.” You are just good enough to meet the task.

- “Actions and awareness are merged.” All of your awareness and attention is directed toward the task at hand.

- “Distractions are excluded from consciousness.” Distractions might be there, but you completely ignore them.

- “There is no worry of failure.” You know you can do it.

- “Self-consciousness disappears.” You’re unconcerned with how you appear to others.

- “The sense of time becomes distorted.” Time seems to either pass more slowly or more quickly.

- “The activity becomes autotelic.” The activity is enjoyed not for the rewards it brings but for the enjoyment produced by doing it.2

Let’s look at some of these in greater detail.

Clear Goals and Focus

Flow cannot happen unless you’re doing something with a clear goal. This clarity of purpose helps you know whether or not you’re doing well. This is essential because flow only happens when you’re feeling successful.

It’s also essential to stay focused on what you’re doing. Flow happens when you lose yourself in a task – when your mind is only engaged in that activity and nothing else, when you lose track of time, when you become completely absorbed.

This goes hand-in-hand with having a clear objective, as Csikszentmihalyi explains:

“The pursuit of a goal brings order in awareness because a person must concentrate attention on the task at hand and momentarily forget everything else.”3

While you’re in flow, you become so focused that nothing else matters to you. Your concentration is so intense that there’s no attention left over for anything else. You can’t think about your problems, worry about tomorrow, or regret what happened yesterday. This is one reason flow feels good – you’re too busy with the task at hand to think about anything upsetting.

Ironically, however, “keeping your eyes on the prize” is antithetical to flow. There is a “prize” – a goal – but your attention will not be on the objective itself; it will be on the process of moving toward that goal. You get into flow by keeping your eyes on the process. For example, if my goal is to create a blog post that will help my readers, I should focus on the process of writing well. Or if your goal is to win a tennis match, you should focus on the process of moving your body and hitting the ball.

Staying present in this way is difficult, but it is a skill that can be learned. Practices such as mindfulness meditation can help train your brain to stay in the moment, making flow come more easily. You should also eliminate distractions in your environment as much as possible. And you should not multitask.

In The Rise of Superman, a book about flow in extreme sports, Steven Kotler points out that we need to continually set targets that are right at the edge of our skillset because, “If the challenge is too easy, we stop paying attention.”1

The Sweet Spot Between Challenge and Skill

Have you ever waited tables? Or worked as a cook or a barista? If you have, this will be easy to understand. If you haven’t, use your imagination.

I used to work as a server and a bartender. If the restaurant was slow, work was easy, but you didn’t make very much money. If the restaurant was busy, work was hard, but you made good money. (More customers meant more tips.) And you might think of this as a direct trade-off, where slow days were enjoyable, and busy days were unpleasant but came with a good payout. The truth turns out to be more complicated though, and flow explains why.

When the restaurant is slow, you’re bored. The task is too easy for your skillset, so you don’t have a chance to shine. When the restaurant gets busier, it becomes more challenging and, as a result, more engaging. You get in the groove. You get into flow. However, if it gets too busy, and you find yourself “in the weeds,” as servers like to say, you become overwhelmed and anxiety takes over. Thus, the best experience for a server is in that sweet spot where it’s challenging but not too challenging because that’s where you can get into flow.

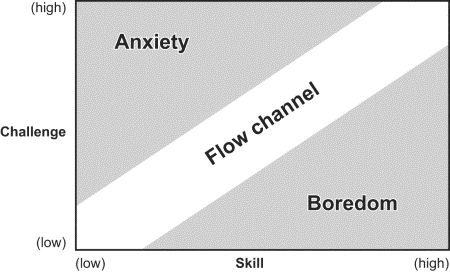

One of Csikszentmihalyi’s insights was that you can locate any given activity for a person on the following graph:

If the task is easy, and your skill level is high, you’ll either be bored or relaxed. You might do the task well, but you don’t feel any satisfaction from it. If the task is difficult, and your skill level is too low, you’ll become anxious, flustered, or frustrated, and you’ll be unable to do the task well.

But when the task is difficult, and you are skilled enough to meet the challenge, you can experience flow. You will get to enjoy the satisfaction of handling something difficult with grace. You’ll probably feel a little impressed with yourself. The success you feel during flow provides a boost to your self-efficacy, which is where true confidence comes from. And, of course, this feels good.

In his book Flow, Csikszentmihalyi notes that:

“In all the activities people in our study reported engaging in, enjoyment comes at a very specific point: whenever the opportunities for action perceived by the individual are equal to his or her capabilities. Playing tennis, for instance, is not enjoyable if the two opponents are mismatched. The less skilled player will feel anxious, and the better player will feel bored. The same is true for every other activity… Enjoyment appears at the boundary between boredom and anxiety, when the challenges are just balanced with the person’s capacity to act.”3

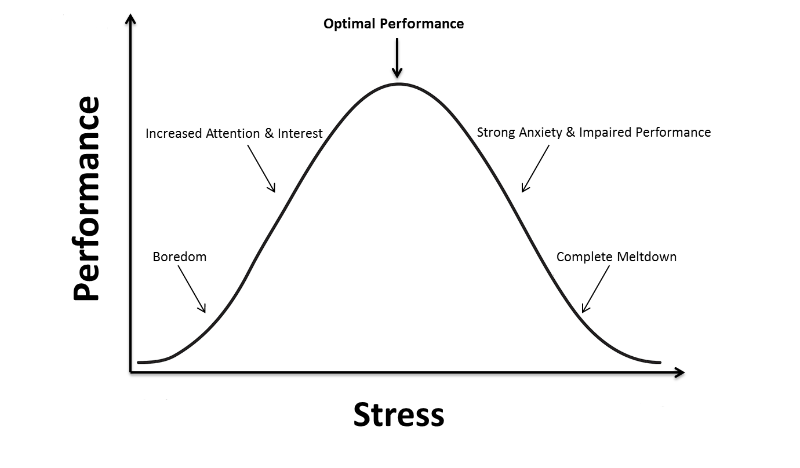

This parallels an idea I discussed in my breakdown of stress. Recall that our performance is highest when we’re experiencing a medium amount of stress:

Thus, we don’t want to avoid challenges and the stress they bring. We want to find appropriate challenges that come with just the right amount of stress.

Of course, the way we perceive a difficult task can greatly influence our response to it. It helps to maintain realistic optimism about your ability to handle the task. And it helps to call upon our Stoic principles and see obstacles as opportunities to grow.

“Of all the virtues we can learn no trait is more useful, more essential for survival, and more likely to improve the quality of life than the ability to transform adversity into an enjoyable challenge.” –Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi3

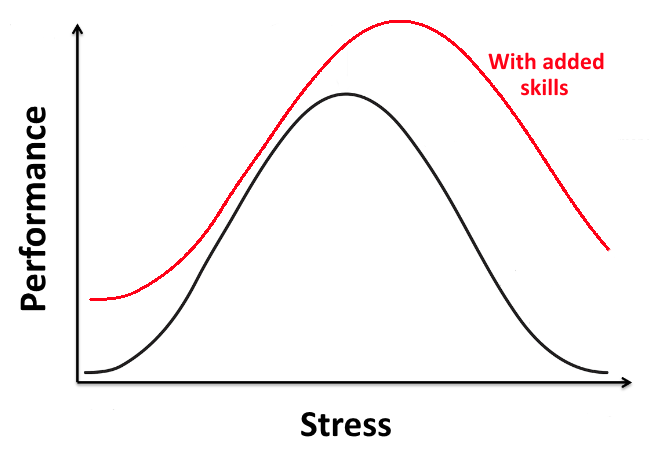

Also recall that, with increased skill, we can handle more difficulty without cracking under the pressure:

And that brings us to one of the main benefits of incorporating flow into your life: mastery.

Mastery and Flow

We can’t experience flow during an easy task, so we have to challenge ourselves and push our limits.

How much should you push yourself? Flow expert Steven Kotler says 4%.1 I’m not sure how exactly you can measure that for any given activity, but the number is still useful. Pushing yourself by 4% means going a little outside your comfort zone – not so far that you panic or fall apart. Pushing yourself by 4% means expanding your skills incrementally – not trying to double your ability overnight.

This is essentially a prescription to engage in “purposeful practice.” In their book Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool detail the science of becoming world-class in domains such as chess, music, and sports. Becoming one of the best in the world requires thousands of hours of purposeful practice in which you “Get outside your comfort zone … in a focused way, with clear goals, a plan for reaching those goals, and a way to monitor your progress.”4

Now, this kind of practice is often described as “ugly” – because you’re working on skills you don’t quite have down – or “tedious” – because it can involve numerous daily repetitions of techniques that aren’t particularly fun. However, when flow comes into the picture, the pursuit of mastery takes on a new flavor.

Flow is such a rewarding experience that, if you can get into flow while pushing yourself to improve, you’ll love practicing your craft. The hard work of developing expertise won’t feel like work at all. It’ll feel like play. And, as a result, you’ll be eager to practice, so you’ll practice more often, and you’ll improve more quickly.

Here’s how Kotler describes it:

“When doing what we most love transforms us into the best possible version of ourselves and that version hints at even greater future possibilities, the urge to explore those possibilities becomes feverish compulsion. Intrinsic motivation goes through the roof. Thus flow becomes an alternative path to mastery, sans the misery. Forget 10,000 hours of delayed gratification. Flow junkies turn instant gratification into their North Star—putting in far more hours of ‘practice time’ by gleefully harnessing their hedonic impulse.”1

Or, in short:

“This means that flow doesn’t just provide a joyful, self-directed path toward mastery—it literally shortens the path.”1

However, I should point out that the flow experience is not always fun or “gleeful” – but gratifying nonetheless. Flow is often marked by gritty persistence. You do the work of overcoming obstacle after obstacle, and though it is difficult, you move forward with unhesitating confidence. While this is not a pleasurable experience, succeeding via strenuous effort is deeply satisfying, and this motivates continued effort.

In any case, with flow, you don’t walk the mastery path begrudgingly – you run down it enthusiastically. And when you do, you become, in Csikszentmihalyi’s words, “an increasingly extraordinary individual.”3 What was once impossible for you – and what seems impossible to others – simply becomes the next step in your progression.1

And this expertise is not merely marked by impressive performances. It is also marked by creativity.

Creativity and Flow

Flow is a creative state. Athletic and artistic innovation occurs during flow. Entrepreneurs and scientists produce new ideas during states of flow.2

Sometimes, I read or hear something that unleashes a flood of good ideas that, apparently, were just waiting for something to release them. The ideas just pour onto the page, in a rushing stream of consciousness. It’s an incredible feeling. This is flow.

Other times, I don’t feel like writing, but I force myself to get started anyway, and after a short while, I get into a groove. Putting ideas into words becomes easy, and one idea just flows into the next. This, too, is flow.

Creativity is deeply satisfying, so this is yet another reason why flow is a positive experience. Most creators pursue their craft, not because of some external goal, but because they derive satisfaction from the activity itself. This is what Csikszentmihalyi meant when he wrote, “The activity becomes autotelic.”2 It is done for its own sake.

One thing that can sabotage creative flow is self-consciousness. If you’re worried about what other people think, or if you’re focused on trying to impress people, you won’t be focused enough on the task at hand to get into flow. As Joseph Gordon-Levitt explained in his TED Talk, craving the attention and admiration of others makes you less creative. By contrast, he argues, paying attention – being completely focused on your work – is what leads to creative excellence.5

Furthermore, an activity that produces flow must be one where you get immediate feedback on your performance – not from other people, but from your own perception of how you’re doing.2 Thus, creative flow requires independent self-esteem. To that end, Gordon-Levitt advises that it is better to see other artists as collaborators rather than as competitors.5

The Necessity of Risk

Both pushing your limits and creativity require taking risks. If you only ever do things you’re sure you can do well, you’ll never grow, and you’ll never do anything original. Flow occurs when you’re trying something that feels like it will be a bit beyond your abilities, but then, in the moment, your abilities expand just enough to make you capable of succeeding. Creative flow occurs when you’re willing to try something new.

Barbara Sahakian, a neuropsychologist at the University of Cambridge, put it this way:

“‘If you’re interested in mastery … you have to learn this lesson. To really achieve anything, you have to be able to tolerate and enjoy risk. It has to become a challenge to look forward to. In all fields, to make exceptional discoveries you need risk—you’re just never going to have a breakthrough without it.’”1

Adrenaline junkies in extreme sports pursue a kind of risk that is legitimately dangerous. But this doesn’t mean they never experience fear. Instead, they use fear as a compass, because they know it points the way to flow.1

But you don’t have to put yourself in danger to experience flow. You simply have to lean into the discomfort of “going for it” when you’re unsure. You’ll feel an aversion to taking this kind of risk, just as extreme athletes feel fear, but that resistance is a compass, pointing the way to growth, creativity, and flow.

Flow at Work

Given how much time we spend at work, it would be great if we could experience flow on the job. Well, good news – we can! And you probably already do, at least some of the time. So let’s talk about some ways you can optimize your work to get into flow more often.

Since flow requires focus, you’d be wise to spend more time in airplane mode. Check email less frequently. Avoid social media and the news when you’re at work. These kinds of distractions tend to linger in your mind, keeping you out of deep focus for far longer than the time you spend actively engaging with them.6 Set aside times for uninterrupted work, and ask the people around you to leave these times undisturbed.

You’re more likely to experience flow if you’re using your signature strengths.7 And since using your signature strengths makes you happier, that’s a double-dose of positive psychology goodness. So identify what your signature strengths are, go out of your way to use them, and try to set up your work so that you spend more time doing what you do best.

You’re also more likely to get into flow when you’re doing something you care about – something that’s meaningful to you. We tend to find meaning in activities that are aligned with our values and serve the world’s needs. Flow, then, is yet another reason to pursue Ikigai.

If you often find yourself in the anxiety zone, rather than in the sweet spot between challenges and skills, then you should adopt a practice of relentless learning and up your skills. On a small level, this happened to me just a few weeks ago. One of my students is taking multivariable calculus, and he’s currently working on 3-D vectors. I knew nothing about the topic, and found myself feeling rather anxious about it. So I dug into some resources, learned the content, and did some practice problems. When I worked on it with him the following week, it was fun! It was still very challenging, but I felt ready and got into flow during the work.

Flow at Home

You should also try to design your home life so you can get into flow more often. On this front, most of us have a lot of room for improvement.

Csikszentmihalyi observed that, ironically, most people are happier at work because they experience flow there more often:

“Thus we have a paradoxical situation: On the job people feel skillful and challenged, and therefore feel more happy, strong, creative, and satisfied. In their free time people feel that there is generally not much to do and their skills are not being used, and therefore they tend to feel more sad, weak, dull, and dissatisfied. Yet they would like to work less and spend more time in leisure.”3

On one level, this is another example of how we’re bad at predicting our future emotions; we’re not in tune with what actually makes us happy. We tend to gravitate toward passive activities that cannot produce flow during our leisure time. (Television, by the way, is not capable of inducing a flow experience.)

On another level, this means we should spend more of our leisure time on projects, puzzles, art, music, cooking, games, and sports – activities where we can get into flow. Spend more time challenging yourself, and you’ll probably be more satisfied with how you’ve spent your time.

This is not to say that you should never relax. We need time for rest and recovery, and a passive activity such as watching a movie or reading a book can be a great way to unwind. This is just to say that we should spend less time consuming what others have made and more time creating something of our own.

Even mundane activities like doing the dishes can be transformed into flow experiences if you do follow Csikszentmihalyi’s guidelines.

First, doing the dishes is so easy that you’ll have to find a way to make it more challenging. You could do this by trying to do them as quickly and precisely as possible. This not only ups the challenge, but also forces you to stay focused and present, which makes flow more likely.

Secondly, when you think of doing the dishes, you’re probably just interpreting it as a meaningless task, but that way of thinking makes it harder to get into flow. Instead, you should connect doing the dishes to the things you care about: having a clean home, eating well, taking care of your family. Supposedly meaningless tasks can be reframed in a way that allows for flow.

Usually we experience flow rarely and by accident, but this does not have to be the case. By knowing the characteristics of flow, we can design our work, home-life, and play-time to have those characteristics more often, and thus experience flow more frequently.

“In many ways, the secret to a happy life is to learn to get flow from as many of the things we have to do as possible. … then there is nothing wasted in life, and everything we do is worth doing for its own sake.” –Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi2

Not All Flow is Created Equal

Video games are designed to induce a flow experience. They give you a series of engaging challenges that gradually increase in difficulty, ensuring that you’re never bored but also never too challenged. That’s partly why video games are so fun and, for many people, addictive.

There’s nothing wrong with occasionally playing video games and enjoying the flow experience they can create, but you need to be aware of the way this kind of flow differs from other, more meaningful kinds.

Although Adam Grant demonstrated that video games can be a meaningful form of flow if they’re used as a way to connect with your family, they are generally a shallow form of flow. Yes, they allow you to get “in the zone,” but the effort you put in doesn’t create any tangible benefits. They don’t make you a better person, they don’t improve your circumstances, and they don’t make the world a better place. More meaningful forms of flow will be connected to self-improvement, creation, or contribution.

We evolved the capacity to experience flow because it helped our ancestors survive, innovate, and thrive. Although we enjoy shallow flow experiences, they are inherently less satisfying than meaningful flow experiences because they don’t align with human nature. So, as much as possible, you should strive for flow experiences that are tied to doing work that matters.

To Flow is Human

Csikszentmihalyi’s research has shown that flow is a human universal:

“The flow experience was described in almost identical terms regardless of the activity that produced it. Athletes, artists, religious mystics, scientists, and ordinary working people described their most rewarding experiences with very similar words. And the description did not vary much by culture, gender or age; old and young, rich and poor, men and women, Americans and Japanese seem to experience enjoyment in the same way, even though they may be doing very different things to attain it.”2

It makes sense that we should naturally like using our skills to overcome challenges in the pursuit of meaningful goals. This is essentially what the human mind evolved to do.

But we do not get to experience flow by default. We have to choose it, and we have to earn it.

Practice your craft to become skilled enough to experience flow at work. Choose hobbies where flow is a possibility. Pursue the things that matter most.

In other words, design your life to create as many opportunities for flow as possible because, as Steven Kotler put it:

“Flow is the very thing that makes us come alive. It is the mystery. It is the point.”1

1 Kotler, Steven. The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance. New Harvest, 2014.

2 Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. Harper Perennial, 2013.

3 Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2008.

4 Ericsson, Anders, and Robert Pool. Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

5 Gordon-Levitt, Joseph. “How craving attention makes you less creative.” TED2019.

6 Newport, Cal. Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. Grand Central Publishing, 2016.

7 Seligman, Martin. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. Atria Books, 2004.