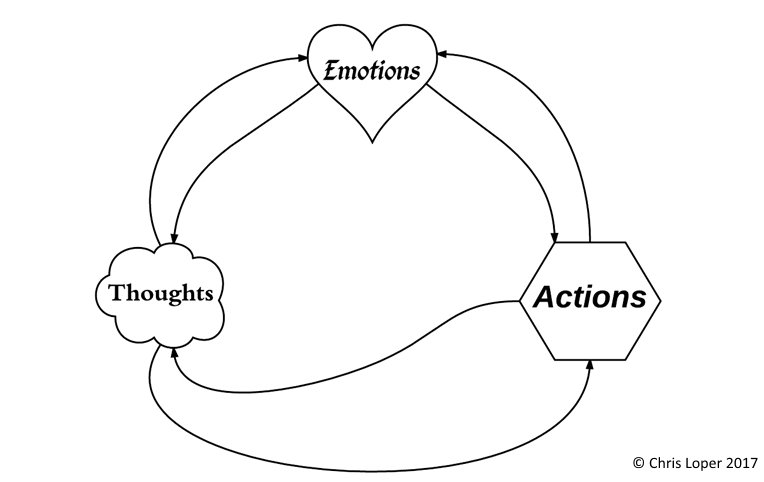

Remember the feedback loop that controls your life?

We’ve talked a lot about how to master the actions component of that feedback loop, and for good reason: Actions are always under our control, and actions speak louder than thoughts.

But thoughts are also important, and we do have some control over them. So it’s time to start exploring the topic of developing better thoughts.

What do I mean by that? I mean developing a better relationship with your thoughts. I mean recognizing and altering your habitual patterns of thought. I mean developing better habits of thought.

If you can learn to get more control over your thoughts, then you’ll tend to have better emotions and better responses to your emotions. You’ll also have an easier time doing the things you need to do. After all, some of your thoughts are excuses.

Now, there are a great many ways to approach this challenge, and I don’t intend to cover them all today. Instead, I just want to introduce you to the most important principle of developing better thoughts, which is also the core tenet of cognitive therapy:

Don’t believe everything you think.

That’s it. Don’t believe everything you think. Our default setting is to simultaneously believe and embody the thoughts that we have. But the thoughts that we have are sometimes wrong, unwise, or unhelpful. So we should not automatically buy into them, and we should not automatically use them to guide our behavior.

Is it Valid?

When examining one of your thoughts, the first consideration is whether or not the thought is valid. Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help with this:

- Is it true?

- Is it supported by evidence?

- Is there counter-evidence to consider?

- Is it logical?

- What biases are reflected in this thought?

- What assumptions are built into this thought?

Often the thoughts we have are only partially true or partially logical. We naturally ignore any evidence that doesn’t support our worldview, so we’re routinely blind to reasons why our thoughts might be wrong. And we automatically imbue our thoughts with our personal perspective, so biases and assumptions are built right in. We judge too quickly. We overgeneralize.

For example, a Democrat might have the thought, Republicans don’t care about poor people. Now, there is evidence to support this viewpoint: the gutting of social programs that benefit lower-income individuals, the sabotaging of the Affordable Care Act, big tax breaks for the rich, and so on. But there is counter-evidence as well. Many Republicans genuinely believe that free-market capitalism and private enterprise will improve the economic prospects of poor people more than government support will. Plus, a lot of poor people vote Republican, and it’s probably safe to assume they care about themselves.

It would probably be more accurate to say that some Republicans don’t care about poor people (I’m looking at you Wilbur Ross), some Republicans believe that the free market is the best way to help the poor, and some Republicans are themselves poor.

Is it Helpful?

Even if our thoughts are valid, they still might not be helpful. Just because a thought is true and logical does not mean you want to act on it, embody it, or allow it to occupy your mind. Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help determine whether or not a thought is helpful:

- Does it make me feel better?

- Does it encourage positive action?

- Does it align with my values?

- Is this the kind of thought I want to have over and over again?

For instance, earlier this week when my internet was randomly shut off, I had the thought, Comcast sucks. This is undeniably true. They have a monopoly in my service area, so they have almost no incentive to provide consistent service or charge reasonable rates.

But entertaining this thought doesn’t do me any good. Since I can’t do anything to make Comcast better, it just makes me feel like a passive victim. So this thought, although valid, serves only to make me less happy. I would be better off thinking about something else.

Replacement Thoughts

Now, if you find that your thoughts aren’t valid or aren’t helpful, you’ll want to replace them with better thoughts. Here are some questions you can use to help with that:

- Is there another way to see this?

- What evidence am I not considering?

- What would someone else say about this?

- What would I say about this if I weren’t personally involved?

- What’s a more helpful way to respond?

- How might this big problem be a blessing in disguise?

- What would an older, wiser version of myself think about this?

- How can I move forward proactively?

- What do I have to be grateful for right now?

Difficulties

There are a couple of reasons why this exercise is particularly difficult.

One is that we like being right. It’s uncomfortable to discover that one of your thoughts is, in fact, wrong. So rather than open-mindedly examining the validity of our thoughts, we usually prefer to just assume we’re right and move on. But if our habitual thoughts routinely lead to unhappy outcomes, then we need to do the uncomfortable work of examining those thoughts.

The second reason why not believing everything you think is difficult is that we’re often unaware of our thoughts. Most of our thoughts arise automatically, and we instantly believe and embody them. We rarely recognize them as thoughts at all. Becoming more aware of your thoughts requires mindfulness, journaling, or the help of a cognitive therapist.

Developing better thoughts is a critical part of becoming better, so we’ll be exploring this in greater depth in future posts. For now, try to practice being aware of your thoughts and having the humility to not believe everything you think.

P.S. Also don’t believe everything you feel.