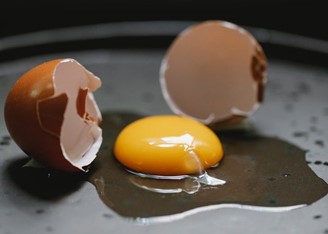

How long does it take to break a glass? How long does it take to clean it up?

How long does it take to damage one’s reputation? How long does it take to rebuild it?

How long does it take to get in a car accident? How long does it take to heal the injured, repair the cars, and process the insurance claims?

Your answers to these questions reveal a deep truth about mistakes and their corrections.

Ruined in an Instant

Some mistakes are very easy to correct, like a miscalculation on a math problem or a misspelled word. Assuming you’re not a rocket scientist or a lawyer, those types of errors are inconsequential and easy to fix.

But many mistakes are very difficult to correct, despite being very easy to make. You can commit a high-cost error in a matter of seconds, but you might spend hours, weeks, or even a lifetime correcting it.

Worse still, some mistakes can never be corrected. Some opportunities are truly once in a lifetime; if you miss them, you can never get them back. If you shatter the marble jar, your relationship will never recover. If you ski off a cliff and die, well, that’s that. Even all the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

Progress vs. Backsliding

Becoming Better is all about moving forward – about making progress on meaningful self-improvement – so I rarely talk about moving backward. But it’s important to avoid slipping backward because, when we do slip, we often slide so far that it takes a tremendous amount of effort to regain the lost ground.

Some backsliding is inevitable, and we shouldn’t beat ourselves up when it happens. But we do want to avoid backsliding whenever possible.

Luckily, most of the time it happens, we’re aware that it’s happening because we’re actually choosing it. And I think we would choose to backslide far less often if we thought more about how difficult it is to recover afterward.

Let’s look at five examples.

1. Losing Weight

This is a goal that I recently adopted for rather unconventional reasons. I have a bad knee and a bad foot, but I love to hike, so I decided that losing five pounds would reduce the impact of each step on my knee and foot. Not a big deal, but over the course of several miles, I think it will make a difference.

I’m already doing the big things right in terms of exercise and nutrition, so this is really about dialing in the details, 1000-Little-Choices style. Losing weight can be difficult and the process can be complicated,* but at the most basic level, it involves consuming fewer calories than you burn. However, dramatically cutting calories is unhealthy and unsustainable, so I’m aiming to come out 100-200 calories ahead most days.

I’m confident that the daily discipline of eating a little less and moving my body a little more will slowly and steadily lead to weight loss. But I’m being careful not to overindulge when I’m at a dinner party or a restaurant. I could easily erase a week’s worth of effort in 30 minutes of overeating. (There might have been a couple of times this winter when I ate 2/3 of a pizza in one sitting.)

So if you’re trying to lose weight, keep in mind that in one meal you could easily eat an extra 1000 or 2000 calories, thus negating ten days of diligently consuming less than you burn. Or, on a smaller scale, you can negate the calorie-burning of a 40-minute workout in a matter of seconds by eating a doughnut. The recovery takes far longer than the error.

Now, when I say overeating is an “error,” I don’t mean that it’s some huge mistake or that it makes you a bad person. But if your goal is to lose weight, you’d be wise to keep in mind the imbalance between mistakes and the time it takes to correct them.

And I’m not suggesting that you should never go for a second helping of pizza or a big piece of cake when you’re at a dinner party. I don’t think you need to deny yourself all the time. But if your social calendar is filling up with events that create opportunities to overeat, it might be impossible for you to both indulge every time and lose weight. You might need to ask yourself, what do I want more? The fleeting pleasure of this dessert, or the lasting satisfaction of sticking with my chosen course?

*Not all calories are created equal. 200 calories of blueberries, for instance, is healthier than 200 calories of candy. The timing and order of food consumption also matter a great deal. Nutrition and metabolism are complicated subjects. Diets rarely work, and losing weight doesn’t necessarily mean you’re becoming healthier. My favorite source for guidance on these matters is Natalie Joffe.

2. Gaining Strength

Ironically, there is one kind of weight that’s easy to lose and hard to gain: muscle.

If you’re trying to get stronger – or if you’ve ever been injured and experienced muscle atrophy – then you probably know that it takes much longer to gain strength than it does to lose it.

When I was 29, I got foot surgery and had to stay off of my left foot for two months. During that time, the muscles in my left leg atrophied. But as soon as I could, I got to work rebuilding that muscle. I’ve since done a tremendous amount of physical therapy, strength training, walking, biking, swimming, hiking, and skiing. Yet, despite all that effort, my left leg is still weaker than my right! That was seven years ago!

Now, you don’t have to get injured to lose strength. You can just stop exercising for a while. Or just stop doing certain types of exercises for a few months. The muscles in your body operate on a simple use-it-or-lose-it protocol (similar to how your brain keeps or discards memories). But while you can lose hard-earned strength in a matter of weeks, it could take years of dedicated work to gain it back.

Similarly, it only takes a few seconds to get seriously injured, but it always takes far longer than that to heal. If I don’t focus on where I’m putting my feet as I go down the stairs, I might fall and sprain my ankle, which will take weeks to recover. (As of this writing, I’ve done this three times in my life, so this isn’t really hypothetical.)

3. Sleep

Perhaps you’ve been optimizing your sleep.

After planning out tomorrow, you let go of work completely when the day is done by staying off of email. In fact, you avoid screen time in general after dinner and don’t use your phone in bed. You eat early too, so ensure that you get a good brain flush. You dim the lights. You have a routine that helps you unwind. Maybe you even tape your mouth shut to ensure that you breathe through your nose. And as a result, you get incrementally better sleep each night.

But then one night, you slip up by allowing yourself to watch a show on Netflix that one of your friends recommended. And it’s really good. So you watch another episode. Sitting on the couch feels good, and Netflix just auto-plays the next episode, so you watch a third and a fourth.

By the time this binge is over, it’s after midnight, but you still find it hard to fall asleep because you’re all jacked up on the drama and the excitement of the show, not to mention the high-energy blue light from the screen. You still have to get up at 6am to get ready for work, so you get a very short night of restless sleep and wake up feeling awful. You resolve to never stay up late binging a show again.

Recovering from sleep deprivation, however, takes a lot longer than becoming sleep-deprived. You can’t just tack on an extra three hours of sleep the next night and get back to normal. It will take several days – maybe even a whole week – of disciplined sleep optimization to recover from this one night of poor sleep.

Again, the recovery takes longer than the error.

4. Addiction

Getting addicted to something is easy. Getting off of it is hard. This is especially true for drugs, where a single dose of an addictive drug can lead to many years of substance abuse and many more years of struggling to recover. And even if you do get sober, The River will always be there, so relapse will always be a risk. (Again, I speak from personal experience.)

But this applies to more than just drugs. Many people are addicted to video games and television shows and social media. How many people have said to themselves, “I’ll make an Instagram account, just to try it out,” and then found themselves totally hooked a month later? How many people have said to themselves, “I’ll download this game and just play a little today because it’s raining outside,” only to wind up spending dozens of hours playing over the coming weeks?

The point here isn’t that you should never try things that have the potential to be addictive. (I mean, obviously, don’t try crystal meth.) The point is that you should only try them in full awareness of what the consequences might be. The earlier example of binging a TV show applies here. If you “just try one episode,” you might get hooked and feel you have to watch the whole series. 30 or 60 hours of your life later, when you finally watch the series finale, you might be glad you watched that one episode, or you might regret getting sucked in.

5. Depression

Becoming depressed isn’t an error, so this looks a little out of place. However, there is a similar imbalance between how easy it is to become depressed and how difficult it is to recover from it.

If I wait until I’m depressed to work on my mental health, I’ll be in a tough position. When I’m depressed, I don’t want to reach out to my social network for support. I don’t want to get professional help. I don’t feel motivated to do any of the things that will probably me feel better. And since I’m terrible at predicting my future emotions, I don’t even see how things could get better.

A much better approach for anyone who is prone to depression is prevention. If I use proven depression-prevention strategies while I’m feeling good, I might avoid becoming depressed altogether and thereby never have to dig myself out of a deep, dark hole.

But Don’t Be Afraid to Make Mistakes

There’s an important caveat to all of this.

My aim here is not to make you risk-averse, so please don’t let this cause you to become afraid (or more afraid) of mistakes and failures.

Mistakes and failures are essential to learning, creativity, and entrepreneurship. You can’t improve at anything – math, art, sports, games, relationships, business – without some amount of screwing up. To err is human, they say, but I prefer the wisdom of the great educator Marva Collins:

“If you can’t make a mistake, you can’t make anything.”1

This article is not about the kinds of errors that might lead to embarrassment or the kinds of mistakes that are inevitable when you try something new. This is about the kinds of errors that create unnecessary and costly setbacks. It’s about the mistakes where we know better – where we know, in the moment, that the choice we’re making isn’t what’s best for us.

And if we can remember just how much time and effort it takes to recover from these errors, we’ll find it a little easier to make better choices.

P.S. This pairs well with The Principle of Two Errors, which is a tool for making better decisions.

1Collins, Marva, and Civia Tamarkin. The Marva Collins’ Way: Returning to Excellence in Education. Tarcher, 1990.