Marcus Aurelius, Roman emperor and practicing Stoic

The Stoics of ancient Rome were a diverse group. On one end of the spectrum, there were people of great wealth and power, like emperor Marcus Aurelius, pictured above. On the other end of the spectrum, there was Epictetus, a crippled former slave. People from all walks of life found value in the philosophy of Stoicism.

The Stoics were not ivory-tower philosophers. They were doers. They embodied their philosophy in the way they lived their lives. Their goal was simple: Live better.

And Stoicism is a set of ideas and practices that remain useful to this day. I have personally employed them for many years to great benefit. And in one form or another, many Stoic principles have already appeared in this blog. But I think it’s time to put them all together into a neat little summary.

Let’s begin with the value of Stoicism.

How can Stoicism help you?

“It’s a philosophy designed to make us more resilient, happier, more virtuous and more wise–and as a result, better people, better parents and better professionals.”1

Stoic principles and practices are all about mental strength and virtue. They will help you assert your willpower in pursuit of your goals. They will help you live up to your highest ideals.

“Stoicism is a tool in the pursuit of self-mastery, perseverance, and wisdom: something one uses to live a great life.”1

Being a “Stoic” doesn’t mean discarding emotions.

This is a common misconception based on the use of the word stoic in everyday English. If someone is “stoic,” it means they have a good poker face – they don’t display emotion. But that is not what is meant by Stoic, with a capital S.

Brian Johnson explains that the “Stoics were not emotionless automatons. They just thought the good life was one in which we experienced a lot more joy and tranquility than anger, anxiety and despair. And, they were willing to do the hard work to create” that life.2

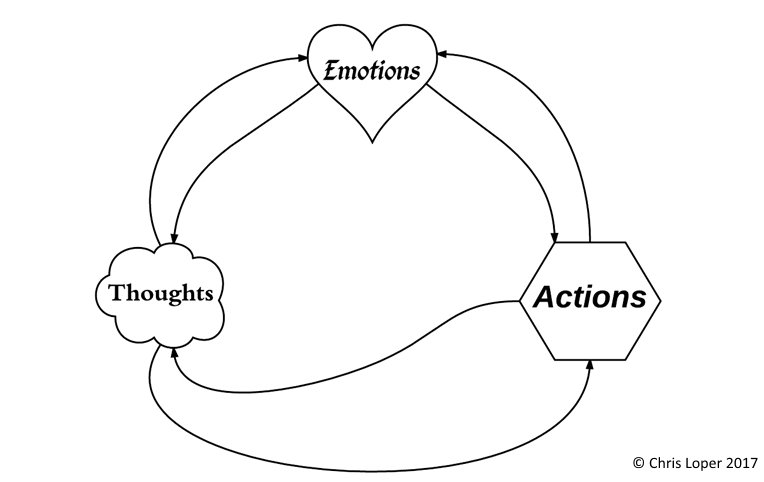

To be a Stoic means, in part, to have greater control over your emotions and to not have your life dictated by them. Stoics focus on the two components of the feedback loop of thoughts, emotions, and actions that can be controlled directly: thoughts and actions.

And that brings us to the first of ten Stoic principles and practices …

1: Focus on what you can control.

“The single most important practice in Stoic philosophy is differentiating between what we can change and what we can’t. What we have influence over and what we do not.”3

We all spend too much time and energy worrying about things outside of our control. And how much time is too much time? Well, anything more than zero, the Stoics would say. Why? Because trying to influence things outside of your control is a futile effort that comes at the expense of taking action on the things you can influence.

Furthermore, just fretting about such things causes unnecessary distress. Here Stoicism aligns with Buddhism, which teaches that suffering = pain x resistance. Acceptance of the things you cannot change is the only logical choice.

“A flight is delayed because of weather—no amount of yelling at an airline representative will end a storm. No amount of wishing will make you taller or shorter or born in a different country. No matter how hard you try, you can’t make someone like you.”3

So learn to distinguish between what you can control and what you cannot control. Wherever you are response-able, that’s where you should focus your energy. In short, this means working on yourself – your own mind and your own behaviors – rather than criticizing what others are doing.1

We’d all be better off, both materially and emotionally, if we spent our time working to improve the things we can influence.

And that leads us to the next idea …

2: Take action.

When you imagine a “stoic” person, in the conventional sense of the word, you might imagine someone sitting indifferently, statuesque, unmoved to action. This is not a Stoic.

The Stoics emphasized taking action. This follows directly from the first principle. Having distinguished between what you can and cannot influence, you pour all your energy into the things you can.

You refuse to be a passive victim of your circumstances. You work hard to make your life better, to make the world better. You are proactive. Even if you’re going through Hell, you keep going.

But action is not to be taken willy-nilly. It must be action with a purpose, driven by carefully chosen goals and values.4

In other words, a Stoic strives to take virtuous action. And that means it’s time to talk about the next principle …

3: Be virtuous.

“A good character is the only guarantee of everlasting, carefree happiness.” –Seneca5

For Stoics, virtue is far more important than pleasure. A good life is a life of virtue. In other words, the path to true happiness is not the selfish pursuit of pleasure, but a values-driven life of integrity, ethical behavior, and service.

Here’s how professor Ward Farnsworth puts it in The Practicing Stoic:

“Stoics regard virtue as sufficient to produce happiness on all occasions, and also as necessary for it. The happiness centrally valued by the Stoic is eudaimonia, or well-being—the good life rather than the good mood. But the Stoic believes that virtue gives rise to joy and to peace of mind as well. Virtue produces these good consequences as side effects. The primary mission of the Stoics, in other words, is to be helpful to others and serve the greater good, and they don’t do this to make themselves happy. They do it because it is the right and natural way to live. But doing it in that spirit, as it turns out, makes them happy.”6

Okay, so living with virtue is good, but what virtues, exactly?

According to DailyStoic.com, the four that matter most are courage, temperance, justice, and wisdom.1

Courage, meaning bravery, does not simply mean the sort of bravery one might display in battle or as a firefighter. It means being willing to face difficult and painful things head-on. That could be an uncomfortable conversation, the loss of a job, or the death of a loved one.1

Temperance, meaning moderation, does not merely mean avoiding alcohol and other drugs, though drunkenness is certainly not virtuous in the eyes of a Stoic. Temperance here means avoiding excess of all sorts: food, luxury, leisure. One can even exercise too much, meditate too much, read too much, work too much, or be brave to the point of foolishness. All these excesses demand moderation.1

Justice means doing what is right, even if it is inconvenient, difficult, or costly. In The Daily Stoic, Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman make the point that this is not all-or-nothing, essentially saying that everything counts:

“Try to do the right thing when the situation calls for it. Treat other people the way you would hope to be treated. And understand that every small choice and tiny matter is an opportunity to practice these larger principles.”3

Okay, but how are you supposed to know what is right? The answer is wisdom.1

Wisdom here means “truth and understanding.” A Stoic should seek to know what is true, learn continuously, and keep an open mind. However, the goal is not to acquire knowledge randomly, but to doggedly pursue the most important facts – those most relevant to living a good life – because that will lead to insights into the true nature of things.1

Marcus Aurelius was making the argument for consuming daily wisdom nearly 2000 years ago:

“Your mind will be like its habitual thoughts; for the soul becomes dyed with the color of its thoughts.” –Marcus Aurelius7

However, living with virtue does not mean becoming judgmental and self-righteous. Instead, your task is to …

4: Lead by example.

“On no occasion call yourself a philosopher, and do not speak much among the uninstructed about theorems, but do that which follows from them. For example, at a banquet, do not say how a man ought to eat, but eat as you ought to eat.” –Epictetus8

The people in your life will learn a great deal more from observing the way you live than from any instruction you might give them. This is not only because mimicking others is the natural way humans and most other animals learn, but also because people get defensive when they’re told what to do.

If a person tells me how to be a better person, the implication is that I’m currently not a good person. I feel judged; I become obstinate. But if a person shows me how to be a better person, simply by the way they live their own life, I might be inspired to follow their example.

My instinct to react defensively when I am taught how to become better is a reflection of my overblown ego. And this brings us to the next Stoic practice …

5: Diminish your ego.

Now, the Stoics operated nearly 2000 years before the advent of psychotherapy, so they’re not referring to the “ego” in the Freudian sense. Rather, as Ryan Holiday defines it in Ego Is the Enemy, ego here means “an unhealthy belief in your own importance. … It’s that petulant child inside every person, the one that chooses getting his or her way over anything else. The need to be better than, more than, recognized for, far past any reasonable utility … It’s the sense of superiority and certainty that exceeds the bounds of confidence and talent.”9

Ego is not reality-based confidence – a.k.a. self-efficacy – it’s a distorted view of your own abilities and significance. It leads to arrogance, stubbornness, and recklessness. “In this way, ego is the enemy of what you want and of what you have: Of mastering your craft. Of real creative insight. Of working well with others. Of building loyalty and support. Of longevity. Of repeating and retaining your success. It repulses advantages and opportunities. It’s a magnet for enemies and errors.”9

So yeah, ego is bad, but how do you diminish it?

I think the best strategy is the “do the opposite” principle I’ve mentioned in the context of overcoming unhelpful thoughts and emotions. Feeling lazy? Do some work. Thinking your partner owes you something? Be generous to them. Consider what your ego wants, and do the opposite of that. Don’t feed it; starve it.

Since your ego is worried about being better than other people, don’t focus on what other people are doing; focus on your own work. Don’t constantly post about your life on social media in order to show off, and don’t scroll through newsfeeds in order to compare your life to the lives of others. Just live your life, for your goals, by your values. In other words, cultivate independent self-esteem.

The ego wants instant recognition. Overcome this by patiently and persistently doing the work that matters most to you without any effort to attain recognition. Doing so communicates to your ego that its desires are unimportant. Each time it hears that message, it loses power. Thus, one mechanical solution to excessive ego is diligently working in obscurity. If you eventually attain prominence or receive accolades, fine, but you’re going to do the work regardless.9

6: You’re not entitled to anything.

“Having an end in mind is no guarantee that you’ll reach it—no Stoic would tolerate that assumption—but not having an end in mind is a guarantee you won’t.” –Ryan Holiday

A practicing Stoic has goals that they want to achieve, and they work hard in pursuit of those goals, but they also know that they’re not entitled to success.

This relates back to the first principle of Stoicism. You can choose your target. You can control how much effort you put in. You can control the strategies you use. But you cannot control all of the variables, so you cannot control the outcome.

You might do everything you can to prepare for an athletic competition, and give it your all, but still come up short of victory. You can spend years writing a book, hoping it will become a bestseller, but there’s no guarantee anyone will read it. You might set out to climb a mountain after months of training and preparation, only to be thwarted by bad weather. You can have a brilliant idea for a restaurant, and begin it with flawless execution, only to have a pandemic shut down your entire industry.

Goals are important, and hard work is critical, but no one is entitled to success.

And make no mistake, diligently working toward an objective that you might never reach is difficult. It requires that you …

7: Exercise your will.

“If there’s a central message of Stoic thought, it’s this: impulses of all kinds are going to come, and your work is to control them, like bringing a dog to heel. Put more simply: think before you act. Ask: Who is in control here? What principles are guiding me?” –Ryan Holiday3

Again, Stoics are not emotionless – they just don’t allow emotions to determine their actions. They strive to do what is right regardless of how they feel. And they do this for two reasons: 1) It’s better for everyone else, and 2) It’s better for them.

“The greatest portion of peace of mind is doing nothing wrong. Those who lack self-control live disoriented and disturbed lives.” –Seneca3

Years ago, before I started strategically cultivating willpower, I was constantly doing things that I knew I shouldn’t be doing. I didn’t live with integrity; my actions weren’t aligned with my ideals and goals. And although I often chose pleasure over discomfort, I was deeply unhappy. It was only when I shifted to a lifestyle driven by values and long-term objectives that I began to feel truly content.

“You have to persevere and fortify your pertinacity until the will to good becomes a disposition to good. How much better to pursue a straight course and eventually reach that destination where the things that are pleasant and the things that are honorable finally become, for you, the same.” –Seneca5

In other words, you can learn to love doing what is right. Your cravings for sugar and fast food and drugs can be replaced with cravings for salads and exercise and nature. Your desire to get what you want can be replaced by a desire to help others thrive. An addiction to binge-watching shows on Netflix can be replaced with a habit of reading.

It’s very difficult to imagine that this is possible, but your brain can rewire. Change your behavior, and eventually, your brain will change too. In the long run, healthy and virtuous behaviors that once drained your willpower become easy and automatic.

And when does willpower matter most?

When things are at their worst. When doing what’s right is most difficult. When keeping your spirits high feels impossible. That’s when you need strong willpower most of all.

8: Practice resilience when faced with obstacles, failure, or tragedy.

“Stoics avoid adversity in the ways that anyone of sense would. But sometimes it comes regardless, and then the Stoic goal is to see the adversity rightly and not let one’s peace of mind be destroyed by its arrival. Indeed, the aim of the Stoic is something more: to accept reversal without shock and to make it grist for the creation of greater things. Nobody wants hardship in any particular case, but it is a necessary element in the formation of worthy people and worthy achievements that, in the long run, we do want. Stoics seek the value in whatever happens.” –Ward Farnsworth6

Ryan Holiday kicked off the modern Stoic revival with his bestselling book The Obstacle Is the Way. The thesis of this book is that problems are actually opportunities for growth. Difficulties, tragedies, setbacks, and failures are all opportunities to learn and become stronger. This mindset will make problems less upsetting, and it will actually make you a better, more capable person.

Here’s how he puts it:

“under pressure and trial we get better—become better people, leaders, and thinkers. … See things for what they are. Do what we can. Endure and bear what we must. What blocked the path is now a path. What once impeded action advances action. The Obstacle is the Way.”4

Believing that problems are actually opportunities is a self-fulfilling prophecy: When you think this way, you will act in such a way as to prove yourself right. When you believe that struggle makes you stronger, you will work to make that vision a reality.

So when something bad happens, say to yourself, “It’s all good mental training.” Epictetus taught that every moment is an opportunity to practice virtue.10 Every difficulty and every temptation is a chance to develop stronger will.

In The Stoic Challenge, professor William B. Irvine points out that there are “ordinary people who have experienced setbacks vastly more challenging than any we are likely to experience, and who, instead of wallowing in self-pity, responded with courage and intelligence. They thereby transformed what could have been personal tragedy into personal triumph.”11 Such examples prove that we can use the bad things that happen to us to become better, stronger, more resilient people.

Now, being human, Stoics are naturally upset by inconvenience, misfortune, and tragedy. But they practice the equanimity game – returning to a steady state of mind as quickly as possible. Marcus Aurelius explained that the more you play this game, the better at it you become:

“When force of circumstance upsets your equanimity, lose no time in recovering your self-control, and do not remain out of tune longer than you can help. Habitual recurrence to the harmony will increase your mastery of it.”7

One of my favorite strategies is to practice non-complaining. Complaining keeps your mind in the state of being upset longer, out of equanimity longer. And what good does it do to complain about things from the past that cannot be changed? Better to spend your energy building a better future. This does not mean you should not speak up against wrongdoing. And this does not mean that you should enjoy setbacks and failures. It simply means that you can learn to accept them readily and then get to work making things better.

“A resilient person will refuse to play the role of victim. To play this role is to invite pity, and she doesn’t regard herself as a pitiful being. She is strong and capable. She may not be able to control whether she is a target of injustice, but she has considerable control over how she responds to being targeted. She can let it ruin her day and possibly her life, or she can respond to it bravely, remaining upbeat while she looks for workarounds to the obstacles that people have wrongly placed in her path.” –William B. Irvine11

9: Choose your response.

“We don’t react to events; we react to our judgments about them, and the judgments are up to us.” –Ward Farnsworth6

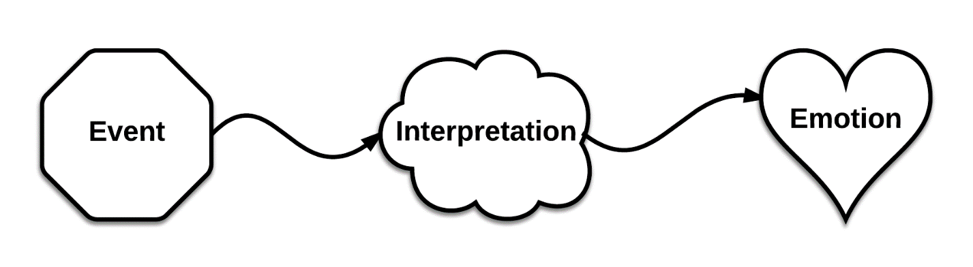

At the core of Stoicism is the practice of responding rather than reacting.

A problem would have you react with frustration? You choose to respond with resilience.

An automatic negative thought arises that would have you react with judgment and criticism? You choose to reject that thought and replace it with a better one.

A feeling of helplessness arises that would have you react with despondency? You choose to take positive action anyway.

If all we do is react, then we don’t have any chance to choose to act in accordance with reason and virtue. We have to create a gap between stimulus and response, and intercede there in order to exercise our free will.

Farnsworth puts it this way:

“The Stoic claim … is that our pleasures, griefs, desires and fears all involve three stages rather than two: not just an event and a reaction, but an event, then a judgment or opinion about it, and then a reaction (to the judgment or opinion). Our task is to notice the middle step, to understand its frequent irrationality, and to control it through the patient use of reason.”6

Sound familiar? That’s because it’s the very model for cognitive therapy laid out in my article on interpreting reality.

Indeed, modern cognitive therapy has roots in ancient Stoic philosophy.12 Furthermore, one of the classic tools of cognitive therapy – taking a different perspective (recall The 3 P’s) – was championed by the ancient Stoics.

Tom Morris puts it this way in The Stoic Art of Living:

“Whenever we are unhinged by a turn of events, it is because we are viewing those events in a very constricted context, from an unduly narrow perspective. In a small setting, anything can look big. But when we mentally step back and set the event disturbing us into a larger and broader contextualization, gaining a bigger picture perspective on it, we find it will not look either as surprising or as big and important. In the grandest scheme of things, our most dreaded obstacles take on a different and much less imposing look.”13

So when you are troubled by some event in your life, look at the big picture. The world is enormous (and the universe is much, much larger). The problems that upset us seem huge and extremely important. Zoom out, and you may see that they are not.

And perspective, done right, should lead to gratitude, which brings us to our final Stoic practice …

10: Be grateful.

“He is wise who doesn’t grieve for the things he doesn’t have, but rejoices for the things he does have.” –Epictetus13

Although the Stoics probably did not keep gratitude journals, they believed in the importance of noticing and appreciating the many good things in life that we tend to take for granted.

A surprising technique for cultivating gratitude is what the Stoics called ‘practicing misfortune.’1

One version of this is to deliberately experience some form of deprivation. Go without food for a day. (This is one reason I fast each quarter). Pretend you don’t have a water heater and take cold showers for a week. Go camping and sleep on the ground. This kind of discomfort training makes you tougher, but, more importantly, it makes you less likely to take everyday comforts for granted. It also helps develop your virtue by cultivating empathy for the millions of people who have to live this way all the time.

Another version of this technique is imagining misfortune. You cannot go out and actually experience losing everything you hold dear, but you can run the thought experiment. Imagine how you would feel if you lost your job, your home, or your partner. If nothing else, it will make you more grateful for what you have.

The most extreme version of this is imagining your own death. Stoics like to say ‘memento mori,’ which is Latin for ‘remember death.’1 One purpose of this practice is to become more comfortable with your inevitable death, so that you do not live in fear of it. Another purpose is to feel more lucky to be alive and, as a result, live better. You could die any time, so be humble and live with virtue today.1

“Take it that you have died today, and your life’s story is ended; and henceforward regard what future time may be given you as an uncovenanted surplus, and live it out in harmony with nature.” –Marcus Aurelius7

In other words, every day is a bonus day.

A more modern version of memento mori comes from Stephen Covey who suggested, in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, that we imagine our own funeral. What would we want people to say about us? How do we want to be remembered? This exercise will help you get clear on your priorities and choose more wisely from among your competing wants.14

You probably want to be remembered as a resilient, hard-working, and humble person. You probably want to be remembered as someone who led by example and lived a life of virtue.

In other words, you probably want to be remembered as a Stoic.

1 “What Is Stoicism? A Definition & 9 Stoic Exercises To Get You Started.” Daily Stoic.

2 Johnson, Brian. Philosopher’s Note on The Stoic Challenge: A Philosopher’s Guide to Becoming Tougher, Calmer, and More Resilient by William B. Irvine.

3 Holiday, Ryan, and Stephen Hanselman. The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living. Portfolio, 2016.

4 Holiday, Ryan. The Obstacle Is the Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials into Triumph. Portfolio/Penguin, 2014.

5 Seneca. Letters from a Stoic. Penguin Classics, 1969.

6 Farnsworth, Ward. The Practicing Stoic: A Philosophical User’s Manual. David R. Godine, 2018.

7 Aurelius, Marcus. Meditations. Penguin Classics, 2006.

8 Epictetus. Enchiridion. Translated by George Long. Digireads.com, 2016.

9 Holiday, Ryan. Ego Is the Enemy. Portfolio, 2016.

10 Pigliucci, Massimo. How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life. Basic Books, 2018

11 Irvine, William B. The Stoic Challenge: A Philosopher’s Guide to Becoming Tougher, Calmer, and More Resilient. W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

12 Robertson, Donald. The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Stoic Philosophy as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy. Routledge, 2010.

13 Morris, Tom V. The Stoic Art of Living: Inner Resilience and Outer Results. Open Court, 2004.

14 Covey, Stephen R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Fireside, 1990.